Freelance Writing Gigs—Foundational to my Career

by Linda Lovas Hoeschler, June 3, 2025

Sometimes the small things in life afford the greatest opportunities. Such were my modest but critical “free-lance writing” gigs.

I never thought of myself as a particularly talented writer, but in the 1950’s school still taught us the writing basics: themes, paragraphing, grammar etc. (Fortunately, my grandsons learned these elements at Montessori school, starting age 5, but few kids seem to learn the fundamentals today.)

The nuns at Transfiguration (K-8) School were unimaginative but gave us the tools to write decently. My mother, an indefatigable reader, also guided me with her final edits. Sleepy Hollow High School, where I was in High Honors classes, challenged my writing (which means challenged my thinking!), and prepared me for college classes at Trinity College in DC and Barnard College in NYC.

However, I was really taught to write thoughtfully, efficiently and with style during the summers of 1964 and 1965 at the Macy chain of papers (Westchester and Rockland counties). After two summers (’62 and ’63) doing ad layout in its Yonkers plant, I was offered a job as an editorial trainee in the White Plains headquarters. I worked under the firm but graceful direction of Ms. Elinor Ney, the editor who ran the “women’s” sections (features, recipes, travel, profiles, etc) for the chain. I believe she also taught some classes at Columbia School of Journalism.

Elinor would assign me interviews of interesting people (our office received many press releases in those days, promoting people, books or events) or topics to cover. I would write my article, and she would stand behind me and mark it up with a red wax pencil. Off it went to the typesetter and transmitter to be offered to one of the dozen+ suburban papers that made up the Macy chain.

Sometimes, but fortunately not very often, Ms. Ney would have me rewrite an entire piece to expose a more compelling “slant.” (I remember her telling another woman in the department: “at least Linda writes well; think of what we could have been stuck with.” (My father was a top executive at the company, so they probably had to take me…at least for a while!)

Scroll down to see some of my summer articles—for which I made about $75 a week!

These 12 weeks of intense newspaper work for two summers apparently provided the credentials to do research and editing/rewriting for my grad school professor, Minerva Morales Etzioni. This lovely Mexican-born professor of Latin American politics taught at the New School where I was studying for my MA on scholarship. Based on a paper I had written for her class, she asked if I might help her footnote and edit a book she was writing.

Dr. Morales then invited Jack and me to dinner at the apartment she shared with her famous Columbia University spouse, sociologist Amitai Etzioni. Our pleasant conversation that evening coupled with her endorsement, (and my Barnard degree, I’m sure) spurred Amitai to also ask me to do some research and writing for him, all for $2 an hour! My work for the Etzionis, 1966 through the summer of 1967, also gave me “stacks” privileges at Columbia where I could check out books for an unlimited time for my own grad school research.

Fast forward to Fall 1969 when Jack and I, 9 months after our move to St Paul, auditioned for and began to sing with the Bach Society. The Society was the major chorus in the Twin Cities at the time, and we performed with the Minnesota Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, plus produced our own concerts (every other year under a week of training by the incomparable Robert Shaw.)

I was disappointed that a Rosalyn Tureck (the “High Priestess of Bach”) March 1970 keyboard concert under the Bach Society’s sponsorship was getting no publicity, so I offered to help. I met with the arts editor of the Minneapolis Star, Peter Altman, to pitch concert coverage. Altman quickly responded, “We don’t have time.” “Nonsense,” I responded, “I used to write for newspapers, and you can make the time for something like this.” Altman quipped: “How would you like to write for us?!”

I think I responded that I didn’t have the training, but he urged me to cover a late March Minnesota Orchestra concert at Northrup Auditorium since the paper needed a reviewer. I bravely accepted. What was I thinking?

I worked hard to prepare for this concert assignment, where Henryk Szeryng performed Bartok’s 2nd Violin Concerto under the baton of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, who also conducted Strauss “Death and Transfiguration” and Mozart’s “G minor Symphony.” I went to the library at the College of St Catherine and got copies of the program’s music scores as well as recordings (to tune my ear to various music interpretations). I would sit by our home turntable, often with Kristen on my lap, and follow the scores while I listened to the recordings.

This started a pattern of spending 20 to 40 hours of preparation for each review (for which I got paid $25 each—in later years, up to a whopping $35.)

This also triggered a recurring nightmare: I would get to a concert but the conductor didn’t show up. The first violin would find me in the audience and say “If you’re so smart, why don’t you conduct the concert!”

Over the years I wrote several dozen reviews and features articles for the Minneapolis Star (occasionally for the St Paul papers, plus a few magazines). My name appeared often enough that people thought writing was my profession.

I couldn’t have done the job without a lot of support at home: Jack, who worked full time at the law firm, Doherty, Rumble and Butler, would accompany me to concerts, then drive me to the newspaper offices in downtown Minneapolis where I would pound out my review on a typewriter. If our babysitter (usually one of the Becker girls from next door) couldn’t stay at our home until 1:30am or so, I would write the review at home and Jack would drive it to the news office, since the review had to make deadline for the afternoon paper. Crazy!

But we were young and energetic, and Jack totally supported my side gig. My review work also benefitted Jack’s career. The law firm partners labeled him “their arts guy” so put him on the boards of the St Paul Chamber Orchestra, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Science Museum of Minnesota and Guthrie Theater, all while in his 20’s and early 30’s. The Twin Cities have always been open to newcomers who are willing to work on behalf of the community, so we were readily embraced and promoted. How lucky were we?!

These periodic newspaper reviews led to other free-lance writing and editing work. Among the free-lance jobs I did:

--award-winning Annual Reports (1972 and 1974) for the St Paul Arts and Science Council;

--a case statement for a campaign to fund the rehabilitation of the historic Federal Post Office and converting it into Landmark Center;

--interviews of Science Museum curators (biology and paleontology) to outline design guidelines for the proposed new museum;

--a case statement for building a new Science Museum and its Omnitheater;

--a grant proposal to fund a new Science Museum and rehab of the Old Federal Courts Building;

--design team work for new Science Museum exhibits (I mostly did labels);

--other grant proposals for the SMM and a care center;

--lectures on music for organizations such as the New Century Club;

--a slide show with narrator and music for the 100th anniversary of Unity Unitarian church in St Paul;

--a Sunday service at Unity Unitarian about Charles Ives; 3 musical soloists or ensembles played some tunes as Ives might have heard them in Connecticut; 3 classical ensembles played the works that incorporated these tunes into them.

--writing/editing an Upper-Midwest landscaping guide by Marion Fry in trade for her designing an engawa, front fence and side garden boxes at 1630 Edgcumbe.

In the late Spring of 1976, David Durenberger (a future US Senator who worked as an assistant to former governor and CEO of HB FULLER, Elmer Anderson) called me at the recommendation of Marlow Burt (CEO of St Paul Arts and Science Council). Durenberger interviewed me and offered me a temporary job: to compile the research and edit a report for the governor on the impact of the arts on Minnesota’s economy. The report was to be the crowning outcome of the prestigious (temporary) Governor’s Commission on the Arts; the commissioners were Minnesota’s leading CEO’s.

Our family was headed West for an extended driving trip and whitewater rafting down the Colorado River, the latter with Jack’s family. I really didn’t want to take the gig, particularly after I met some of the so-called research staff. (Having done original and statistical research in college and grad school, I didn’t think the staff really knew what they were doing.)

But when Jack challenged me by saying I was afraid of full-time work, I reluctantly agreed to the editorial role, AFTER our vacation.

Mid-July I went to the GCA office and quickly deduced that my first impressions were correct: little of the “research” was scientifically constructed, and NOTHING had been written for me to edit. Many of the employees were artists who knew nothing about economic impact nor about writing. Moreover, the purported ED seldom showed up for work!

I called Durenberger with my conclusions and told him I should leave; that same night, Jimmie Powell, the one other employee with an economics and statistical background, called Durenberger and told him I was the only hope to pull this off. After all, the Commission of community leaders had been meeting monthly for over a year and were supposed to be wrapping up and getting a report to Governor Rudy Perpich. This could be an embarrassment at best, a scandal at worst.

Reluctantly I agreed to pitch in. I went to work very full time (80 hours a week from July 1976-March 1977).

I dismissed the GCA staff, but for one free CETA worker, a secretary, Jimmie Powell and me. We worked like dogs and ended up producing a 278-page report (but you can read the highlights here) that the NEA used as a model for other states’ studies. (I was also disappointed that Durenberger never fessed up openly to the failures and continued to give credit to the worthless ED of the operation. Clearly, a life in politics was not for me!)

But the good news was that this killer of a job (Jack managed the kids’ activities and household help—but I realized I missed a year of Kristen and Fritz growing up and vowed never to do this again, a promise I kept) led to two job opportunities offered by members of the Governor’s Commission. Bill Spoor, CEO of Pillsbury, asked me to join its management team; Ken Dayton recommended that I join the newly formed Dayton Hudson Foundation (DHF) as the half-time Arts Grants Coordinator.

Because I didn’t have the child-care and household management operations figured out, I interviewed for and was accepted at DHF, starting April 1977. This was my Miss America job if ever I had one!

I traveled around the country, discussing arts issues and awarding grants—and guess what: everyone thought I was beautiful and talented. Hah! At the time, the Dayton Hudson holding company comprised 13 companies (Target, B Dalton Bookseller, etc.), and since DHF was usually the lead donor in our business locations, there were many opportunities to learn from and help arts groups and civic leaders leverage our donations.

About 10 months into the job, Dayton-Hudson corporate Personnel called me to interview me to head Communications (relations with financial press such as the WSJ, Fortune, Forbes, etc.). Because I had written for newspapers over the years, I was considered a worthy candidate, and besides, the company wanted a woman to head this “pyramid”; (other pyramids included Finance, Control, Legal, Personnel.) Moreover, Communications was considered a frustrating underperformer, so hiring me seemed a risk worth taking!

On April 1, 1978 I started my new job as Director of Communications, and two years later became the first female VP of Dayton Hudson Corporation, a $7billion a year operation. This led to a challenging management career in retail (DHC and B.Dalton), computers (National Computer Systems) and composers (American Composers Forum).

My substantial and fortunate career had been launched from a solid, but spotty career of free-lance work. Who would’ve thunk?!

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1964_06_26_6

The_Herald_Statesman_1964_07_09_14

The_Standard_Star_1964_07_15_44

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1964_07_16_6

The_Standard_Star_1964_07_28_14

The_Standard_Star_1964_07_29_19

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1964_07_30_5

The_Daily_Item_1965_08_04_10

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1964_08_08_5

The_Standard_Star_1964_08_13_14

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1964_09_04_6

The_Herald_Statesman_1964_09_09_29

Mount_Vernon_Argus_1965_06_08_10

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_06_17_15

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_06_24_3

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_06_25_5

Mount_Vernon_Argus_1965_07_08_22

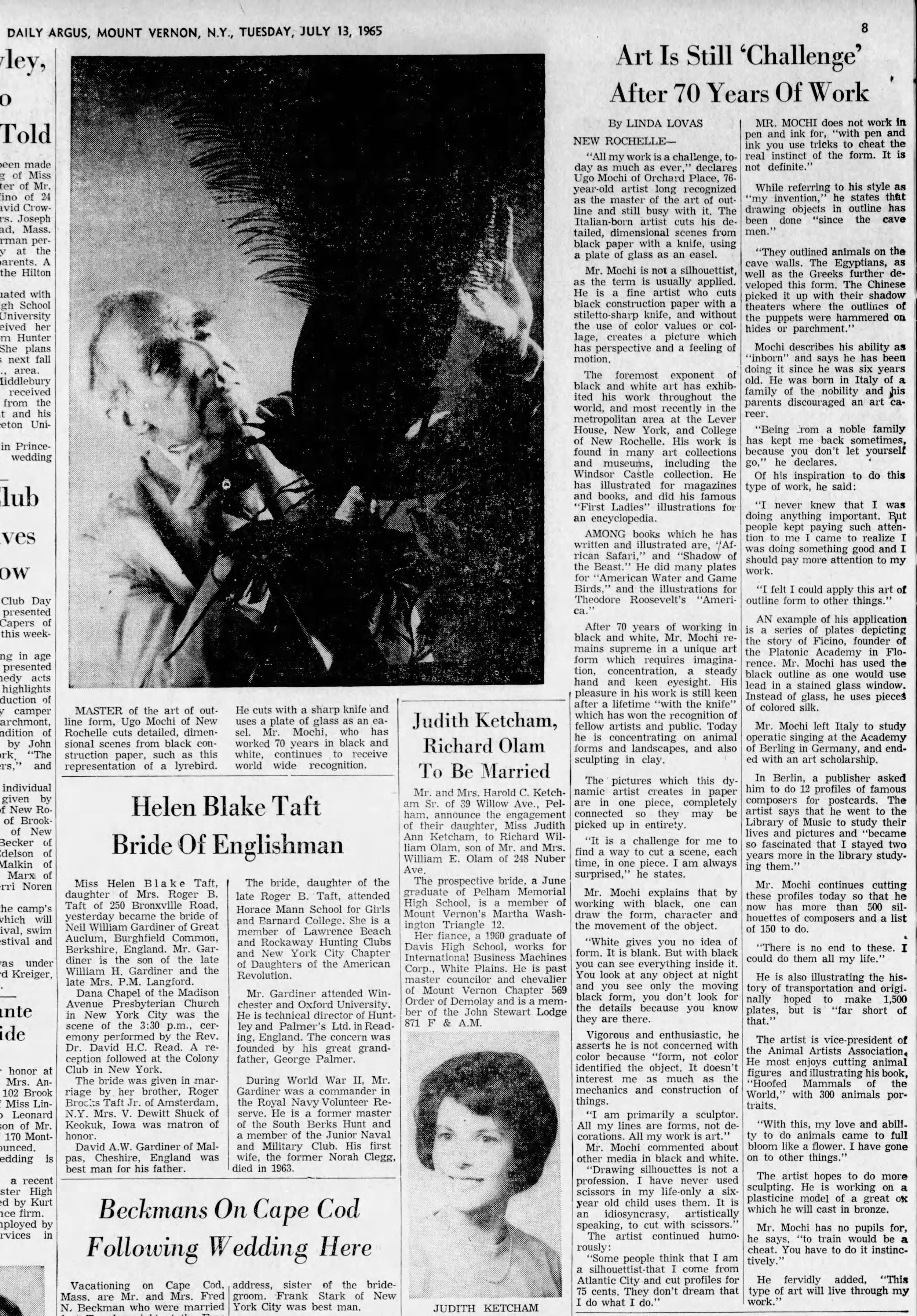

Mount_Vernon_Argus_1965_07_13_8

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_07_15_5

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_07_23_6

The_Standard_Star_1965_07_23_14

The_Standard_Star_1965_08_21_5

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_08_25_24

Mount_Vernon_Argus_1965_08_31_10

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_08_31_10

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_09_01_11

The_Standard_Star_1965_09_07_12

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_09_09_13

Mount_Vernon_Argus_1965_09_15_16

The_Reporter_Dispatch_1965_09_16_15