Jack Hoeschler’s Legacy: Building the Science Museum (1973-78)

by Jack Hoeschler*, 2018

In the early 1970’s, I was a young lawyer with Doherty, Rumble & Butler (DR&B) the oldest law firm in the state. I was asked to help the Science Museum of Minnesota (“SMM”) by Gene Warlich, a more senior lawyer whom I believe had served on the SMM board. The museum shared space in the St. Paul Arts & Science Center on 10th and Cedar Street but needed more room for its expanding program.

Most importantly, the Museum board, led by Ed Titcomb, wanted to build a new “Omnitheater” as part of the expansion. The “Omnitheater” was a combination planetarium on a 45° angle and a large format film theater that would use the new 70 mm/15 perf Imax film format that had been developed in Canada after the Montreal World’s Fair. The first use of an Imax projector was at the San Diego Space Center. SMM would likely be only the second user of this new and exciting format.

It so happened that I was already acquainted with many of the details of what the Museum was planning because my wife Linda had been previously hired by the Museum to help its curators articulate their visions for their various exhibit halls. I had helped edit Linda’s “scripts” for these exhibits and for the Omnitheater facility itself. That detailed knowledge proved crucial later in the planning process.

My first job was to draft a contract with Hammel, Green and Abrahamson (HGA) the design architects chosen for the project. I was also tasked with negotiating an air rights agreement with Sherman Rutzick, the city’s designated developer of the square block directly west of the Arts & Science Center. It was contemplated that SMM would keep its existing space in the Arts & Science Center and join that by skyway with a new three story building in the easterly 1/3 of the Rutzick block. Initially, Rutzick was to be the builder and landlord of the new SMM expansion.

Fairly quickly it became clear that the needs of the museum for a special purpose building and the interests of a commercial landlord were seriously incompatible. SMM’s building could not be easily adapted to commercial use should the museum default on its lease.

Our negotiations with Rutzick were further complicated by the fact that the subsurface area would be used by a municipal parking ramp and the Rutzick buildings and the museum would be constructed on air rights over the garage. Similarly, Rutzick had gotten rights from the city to develop the block based on certain assurances he had made to the city to build a medical office building and an apartment tower, all of which, with the museum, would be connected by an atrium which could be used by each of the constituent structures and their owners.

Needless to say, it was a fairly complicated and interconnected project that required detailed coordination to avoid problems at the interfaces. As a result, my role as lawyer of the museum was significant. Once the HGA contract was signed, museum staff and the architects held weekly planning meetings to work on the design development stage of the work. Without my request, I happened to be copied on the weekly notes from the meetings.

After about two months it became clear to me that no one from the museum was riding herd on the planning process. Various department heads would have a new, good idea and the architects would promptly incorporate that idea into the plans. But no one was watching the budget and the inevitable additional costs of these various ideas. It fell to me to blow the whistle and challenge this runaway process.

As a result, I was invited to join the weekly meetings and act as something of a project coordinator. It turned out that I had a better understanding of the entire project than the individual department heads – all because of my editing of Linda’s scripts for every part of the museum.

The Director of the Science Museum of Minnesota, Phil Taylor, was happy for the help because he lacked experience on such a big real estate project and was spending 110% of his time raising money. Four months in, feeling the stress of constant fundraising, Taylor announced that he no longer wished to function as the CEO and that the board should hire a paid President (Taylor would continue to run the science-side of the Museum) Suddenly, the staff started coming to me with operating questions. Overnight, I became the defacto CEO because I would make decisions. By now I was being paid for my technical work, but not my Board and “ideas” work.

Before the museum could be built, however, we had to deal with the realities of excavating a three-story parking ramp below street level. You would think, digging a deep hole would not be so tough. But it turns out that downtown St. Paul rests on a cap of 10-15 feet of limestone, which is very hard.

In fact, 12,000 years ago, there was a waterfall in St. Paul bigger than Niagara Falls. This eventually receded up the river to the present location of St. Anthony Falls in Minneapolis. The cascading water would scour out the soft sandstone beneath the limestone, the cantilevered limestone cap would fall off, and the falls regressed upstream.

Rehbein Construction contracted with the city to excavate for the parking ramp, but first they had to blast through that limestone cap once all the old buildings on the site had been removed.

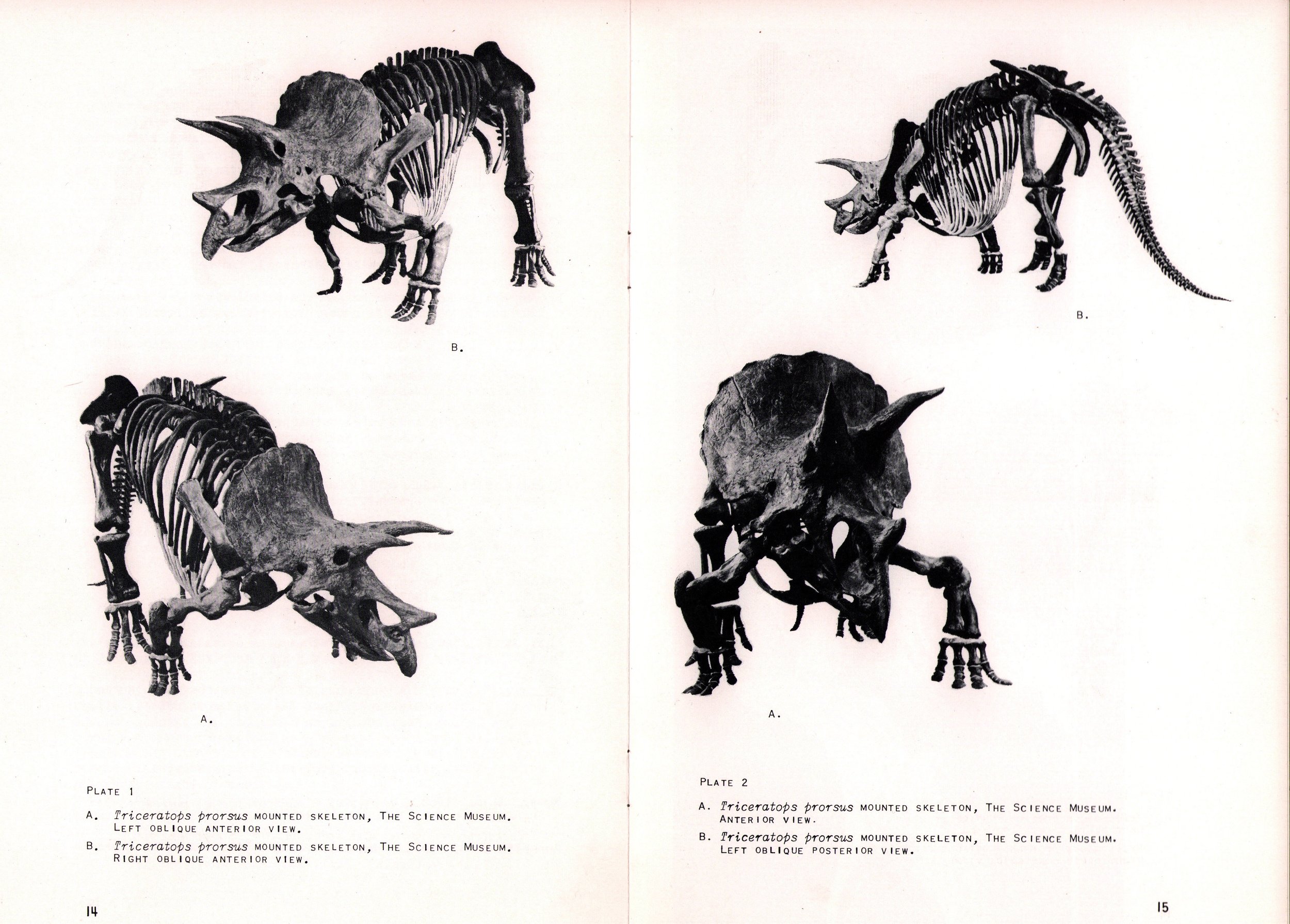

Well, across the street was our treasured Triceratops, one of the most complete specimens in the world. It was supported on a rigid, steel armature. Each time a blast went off, the ground shook, the poor thing shook even more violently.

Bruce Erickson, the paleontologist for the Museum, called me in a panic exclaiming that the blasting was breaking up the beast. So, I ran up to the museum to take a look at the problem in person.

Immediately, I called the general contractor. STOP the blasting! I asked Bruce how long it would take to dismantle the beast… one year! Well, it was the 1970’s, inflation was at 18% so we had to keep going. What to do?

Bruce was scheduled to travel to Florida for two weeks to study crocodiles, so I told him to go, we would take care of his beast for him. We met with the contractor who was legally liable for any damage caused by the blasting. We had to solve this problem fast because I knew that when Bruce returned he would chain himself to the beast if need be, to protect it.

I needed a paleontologist and in a hurry. I called the Natural History Museum in New York City and the Smithsonian. What I learned was that it had been three generations since anyone there had put together a dinosaur. They just dust them now.

There was a guy in L.A., a small bone dinosaur expert, who wouldn’t go outside his world and in an offhand statement said, “They all come broken anyway, what the hell.” That did not make me feel any better as a plaintiff’s lawyer. But he did tell me about a guy at Brigham Young University, Jim Jensen. He turned out to be a home run.

There was also an engineer in Minneapolis who had worked for the Atomic Energy Commission measuring damage from atomic blasts, so I hired him to assess what we were up against. The next day, Rehbein’s insurance company called him to be their expert but we had already retained him, thank goodness.

We showed him the situation, he did his measurements and gave us a very detailed evaluation of the pressure on the victim. He came up with a plan to build a structure that would cushion the beast. He estimated it would take a month, and cost $65,000. Yikes.

Meanwhile, I had called Jensen and invited him to come. He was a real Eric Hoffer character, the common man scientist and philosopher. He had never graduated from high school but had learned all his paleontology working on digs and now had a couple of honorary degrees in recognition of his work. He had nothing but practical wisdom. My kind of guy. He looked at the situation, then asked me to get him a house mover. Together they proposed to build a steel A-frame over the beast from which it would be suspended with seat belts, taking the weight off the armature and allowing it to flex with the blast pressures.

At the time there were newspaper articles galore, and we had grade school kids writing… “Save our Triceratops.” We even had a guy from North Dakota sending us rocket silo padding.

Of course, I kept Bruce apprised of what we were doing to save his child. Bruce knew Jensen and was okay with him.

I worked a deal whereby we (The Museum) would take the risk of further damage and Rehbein’s insurance company would pay us the $65,000 it would have cost if the atomic engineer’s plan had been adopted. We gave the cash to the Museum’s paleontology department. Bruce was happy on all fronts—and the beast held up nicely after that.

Once it was known that we might get money, Max Lein at the Minnesota Museum of Art wanted insurance money for his pastels that he claimed might have been shaken by the blasting. Well, I put a stop to that by convincing the insurance company to ignore the shakedown.

Now for the next crisis….

One of the key elements of the new museum was building the Omnitheater. At the time, it was only the second one in the world. The first was in San Diego, though before we were finished, Monterey, Mexico built theirs.

But to have a theater chain of only three meant we had to get into the business of promoting the development of other Omni theaters because the large format film was very expensive to use. The Omnimax/Imax projector system was made in Canada where these highly specialized cameras were invented. Just the film itself, before there was anything on it, cost $200,000.

The dome was to be built by a company out of Philadelphia, which had never delivered a system without problems. But they were our sole source for the planetarium hardware and later its maintenance. I made sure we had a contract that would also monitor how much and when they would be paid based on their progress and the performance of the equipment. We had a volunteer group of advisers from 3M and Control Data for all of this kind of technical stuff.

Now it was late in the game. The supplier sent the dome to us in compound curved pie-shaped panels. We had spent $50,000 to rent the extensive scaffolding that was needed to put the panels in place. But once they were assembled overhead, you could see the grey color across the panels was not uniform. It reflected a mosaic which would have been bad when we projected onto it.

To fix this the supplier then told us to spray a highly volatile etching compound onto the screen. But they warned us to be careful because it would explode at 82 degrees or higher. So, all possible spark sources from lights and other switches had to be disabled. We even had to use explosion proof lights to do the work.

I called 3M for advice. No one would stick their neck out. Everyone was in their specialized silo and afraid of a bad result if they were wrong.

Finally, I said, we are going ahead. We were paying penalties for keeping the scaffolding and, we were opening in a month. I called lots of painting contractors. They all said no. Finally, I found someone brave enough to do it. On THE day, he was alone; we all stayed away, me included.

In the end it was a huge success. At the opening in 1978, the new Museum President, Dr. Wendell Mordy, was kind enough to call it, “The House that Jack Built.” I was slightly embarrassed because there were many who worked hard to raise the money that made it a reality, but was still proud of our work.

Twenty years later, the museum had once again outgrown its space and a new building was needed. That is the building you see today on Kellogg Blvd. By then I was Chair of St. Paul Riverfront Development Corporation.

For the first time in two generations, we had a chance to reconstruct the riverfront and reclaim it from the receding industrial glacier that had covered it. We lobbied hard to ensure that the critical mass of cultural entities stayed on the city side of the river and that has worked.

This time the Triceratops was disassembled before it was moved and is now fully assembled greeting all its admirers.

The moral of the story for me and what I tell young lawyers is…

It is important to think like a utility infield baseball player. You should be ready to play all the bases. The world is full of specialists. Don’t make your work so narrow that you will be out of work when trends shift.

Learn about the numbers as well as the law. Because I was able to understand the legal issues and municipal bond financing requirements, I could play in the cracks between the specialties and make connections.

Don’t be afraid to get out of your office. I loved clambering around the new building. You can make adjustments when you are around the site and see things coming at you before they become a crisis.

Be open to the adventure of it all. I ended up owning an Omni Theater in Seattle next to the aquarium. In 1982, I resigned from Doherty, Rumble and Butler and set up my own practice, so I could keep being the lion at the table. It’s fun.

* Jack used Carol MacAllister’s research reports as the basis for expansion into this essay.