Media

Tarrytown Daily News, July 10, 1958

1958

The_Standard_Star_1965_09_07_12

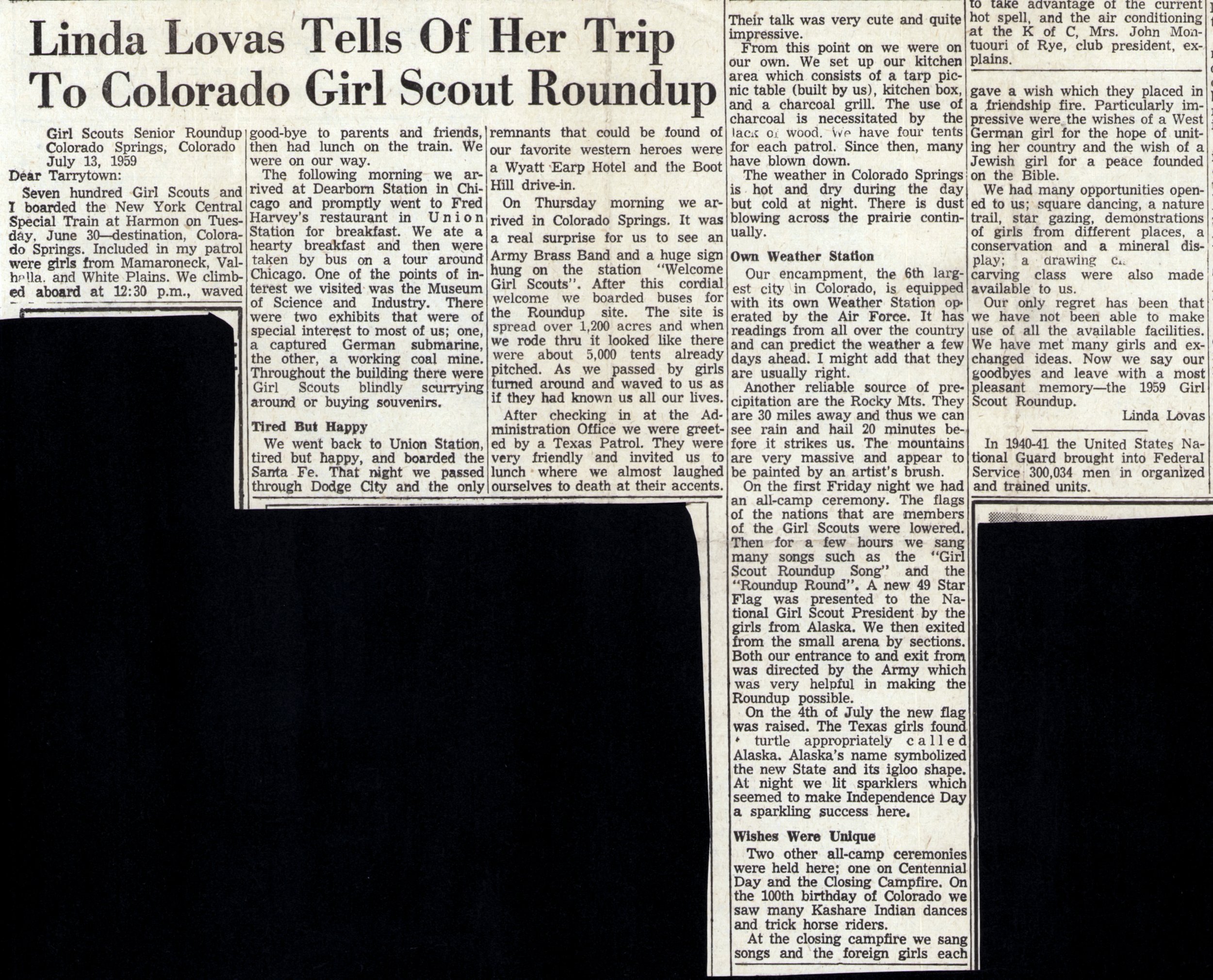

Tarrytown Daily News, 1959

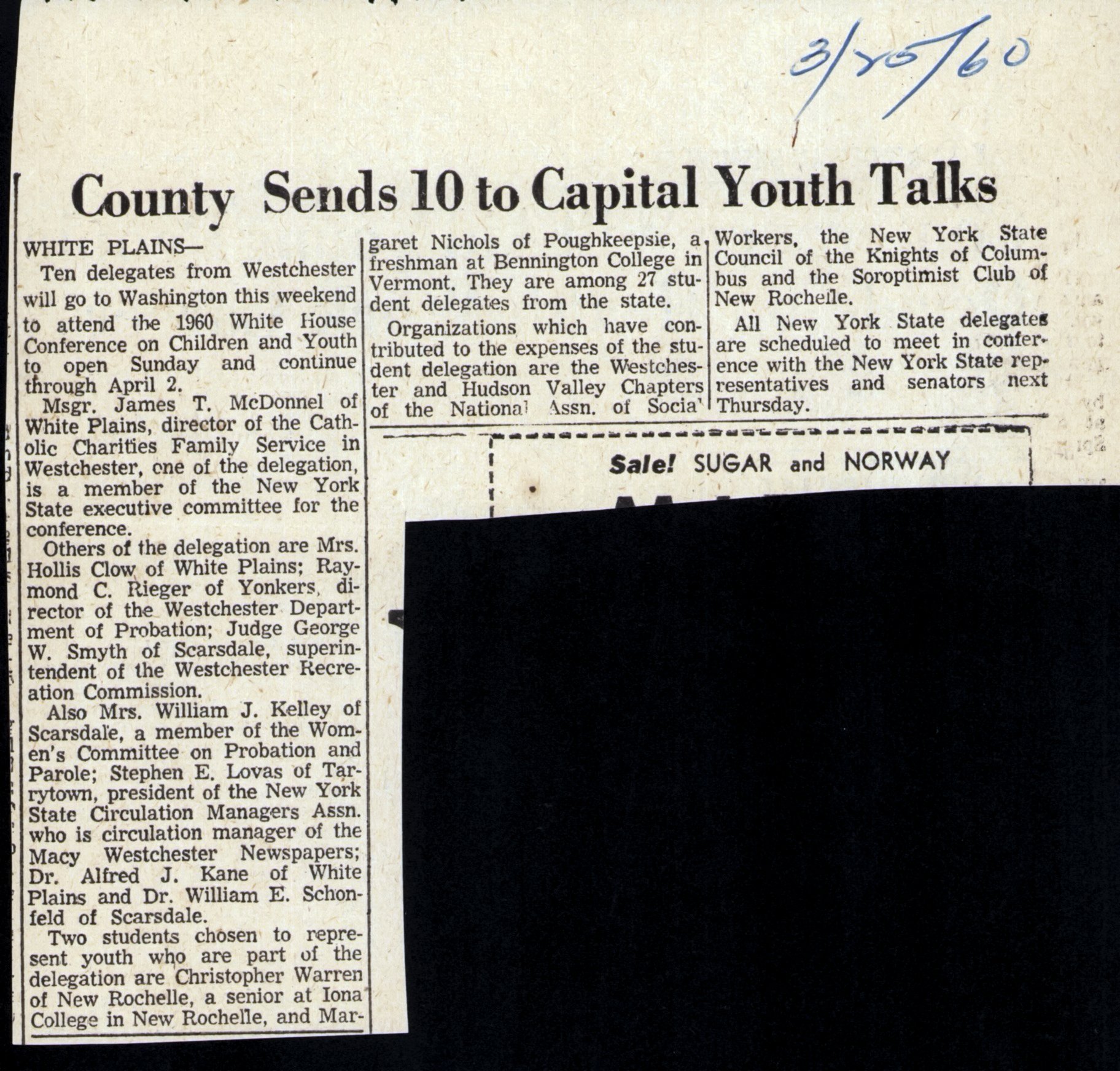

March 25, 1960

Tarrytown Daily News, February 24, 1961

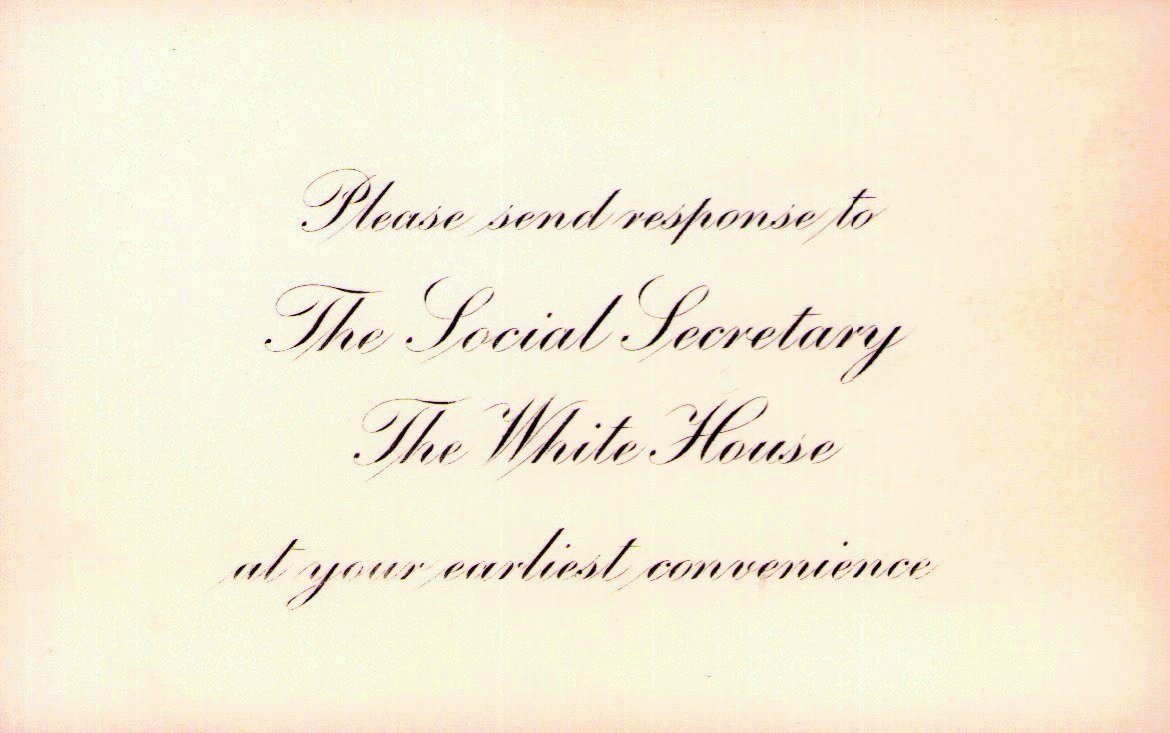

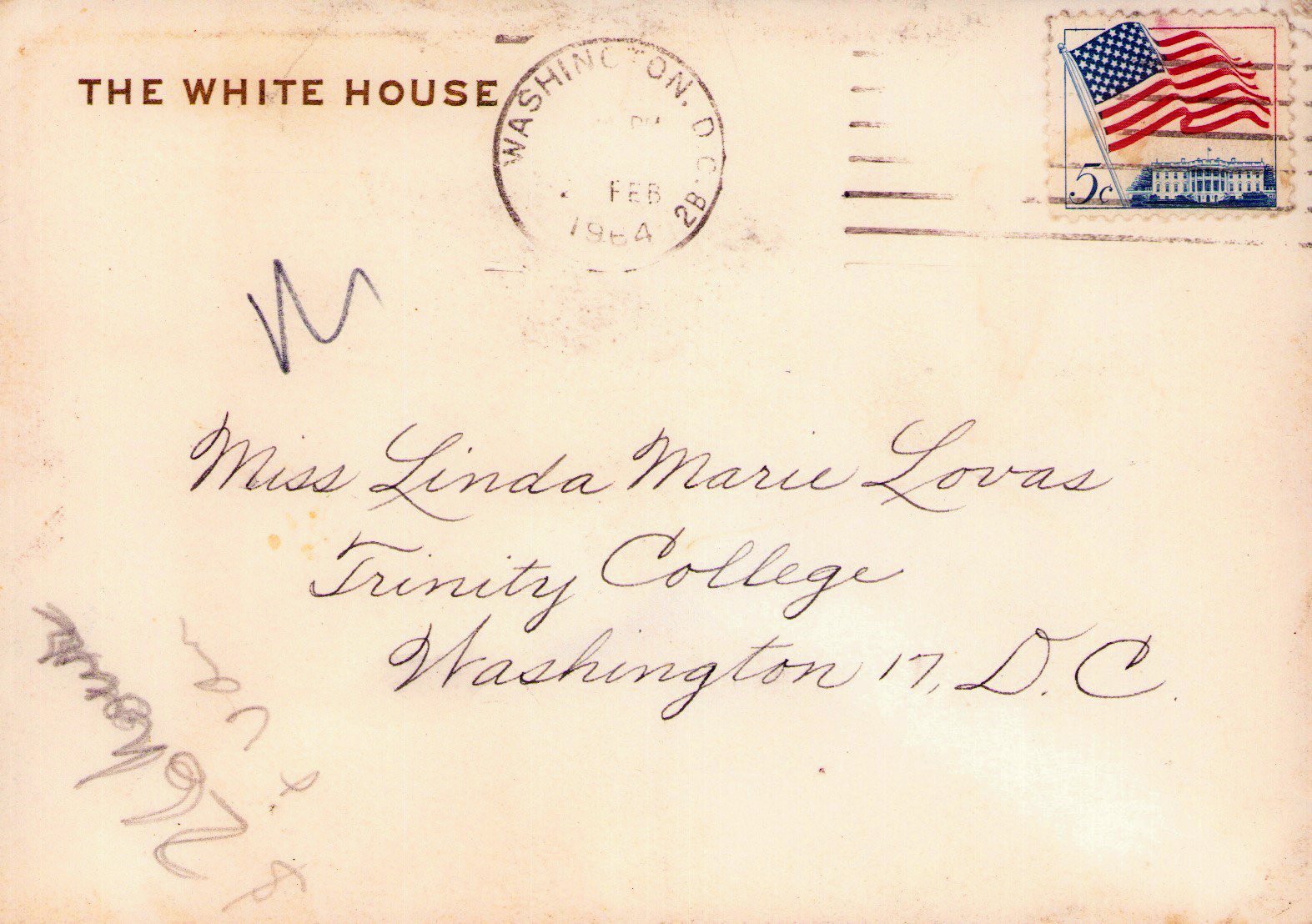

May 12, 1964

Tarrytown Daily News, 1962

September 12, 1964

Tarrytown Daily News, October 30

Tarrytown Daily News, May 8, 1963

Tabor Beacon

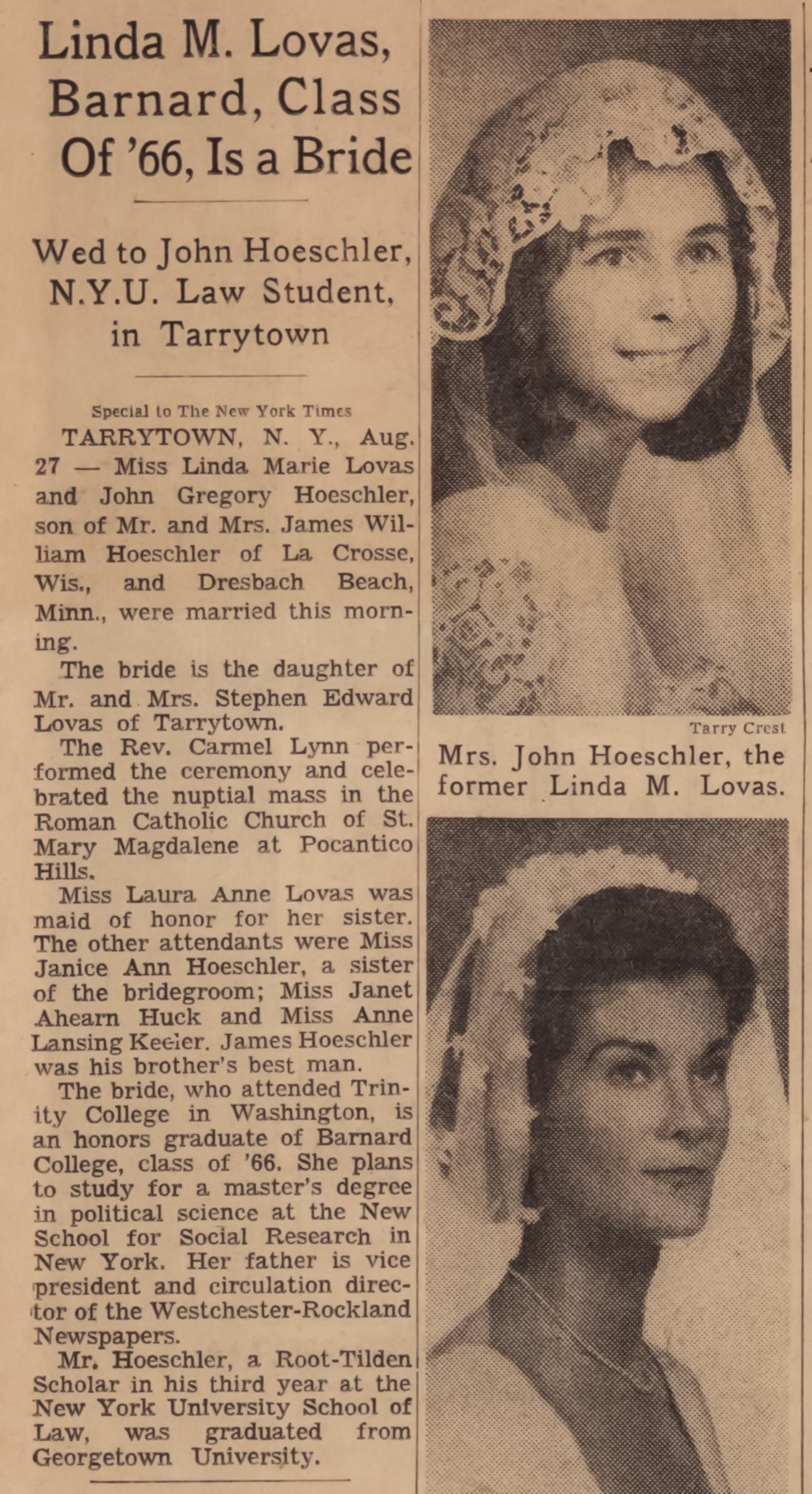

The New York Times, August 28, 1966

April 10, 1968

Tarrytown Daily News, June 2, 1968

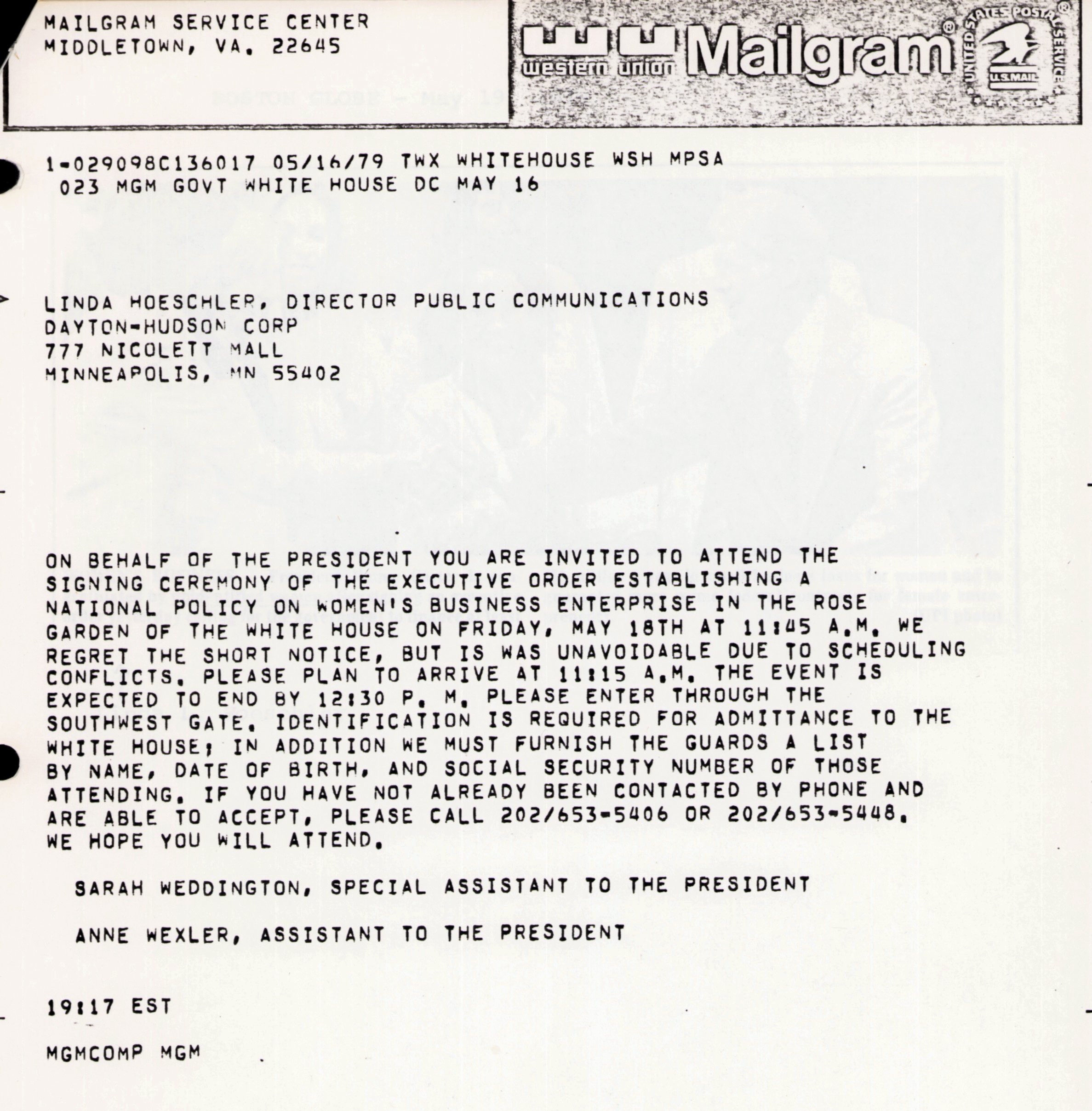

May 16, 1979

Boston Globe, May 19, 1979

Beta Gamma Sigma Spring Banquet, St. Cloud State University, April 17, 1982

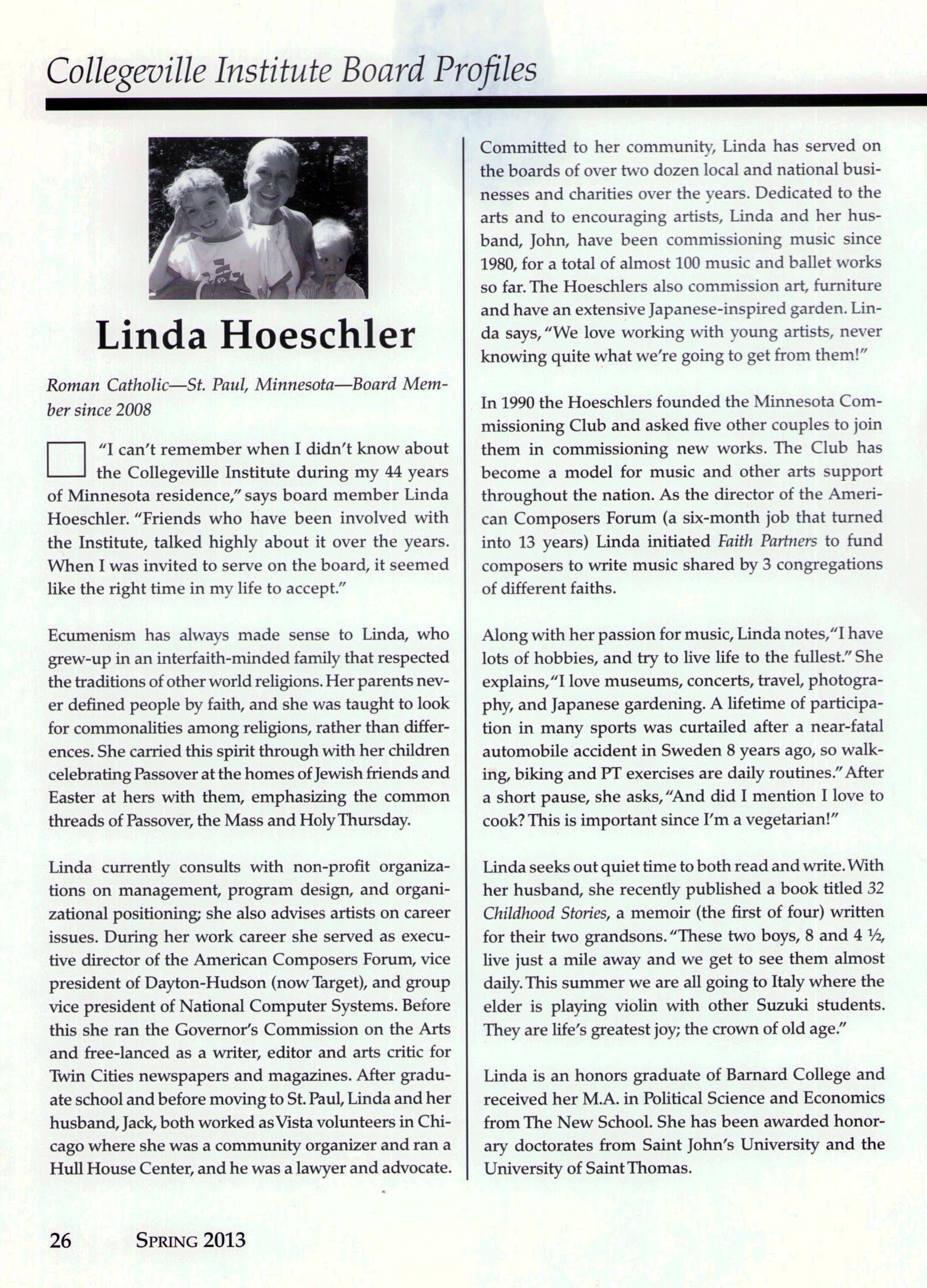

The Women of the Saint John's Bible: A Profile of Linda, December 13, 2024