Music Fit for a King, Written for a Dentist

by Anne Midgette, The New York Times, January 23, 2005

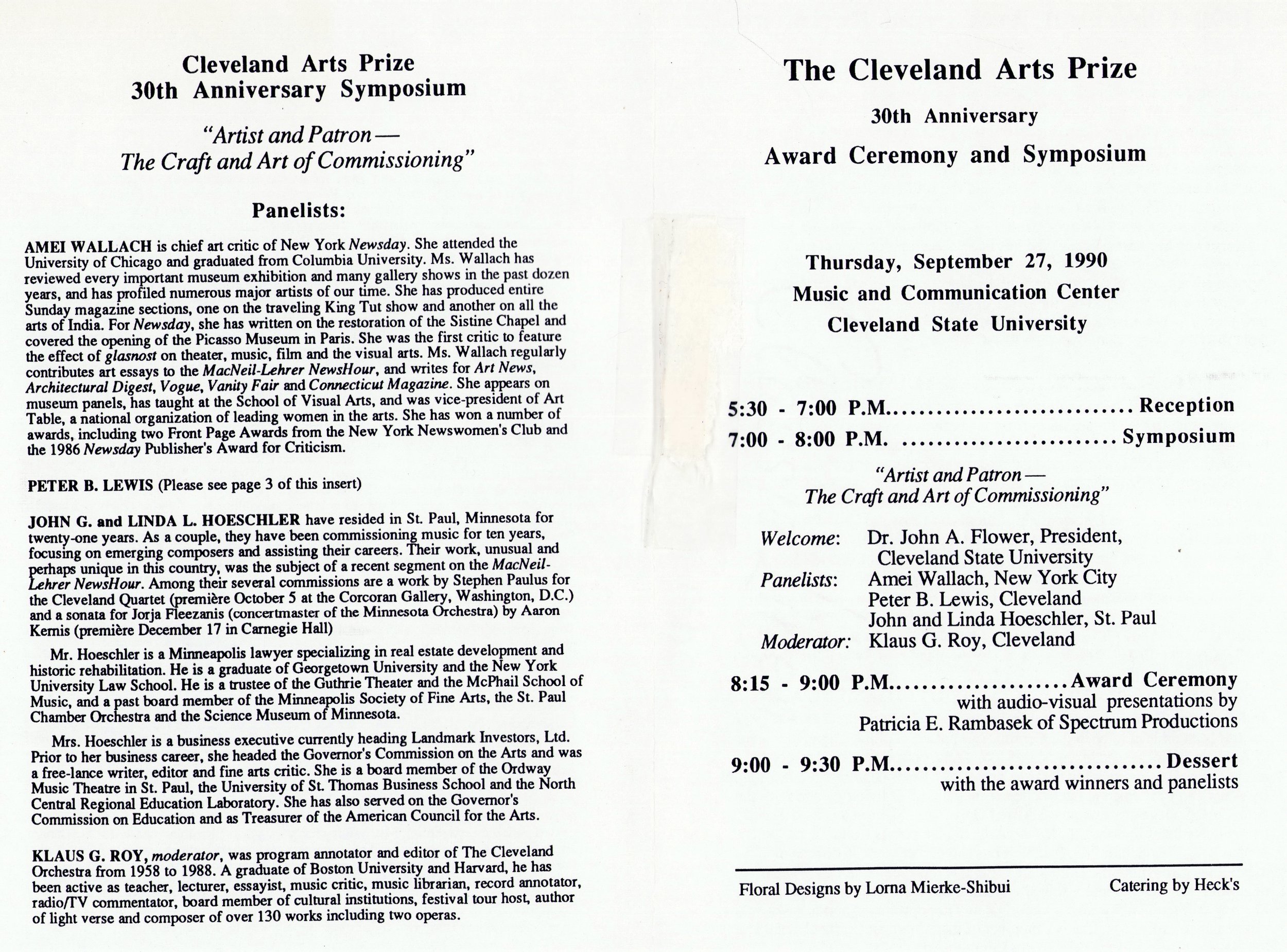

JACK and Linda Hoeschler had a wedding anniversary coming up. Not just any anniversary: it was their 15th. To celebrate, they considered having a tea dance, since they first met at one. But they also wanted something more for their guests and for themselves.

Mrs. Hoeschler, who was working at the Dayton Hudson Foundation in Minneapolis at the time, had an idea. She had recently advised the two composers who had founded the Minnesota Composers Forum. Why not, she suggested to her husband, commission a piece of music from one of them?

The Hoeschlers’ two children play flute, oboe, cello and piano, so Mrs. Hoeschler asked Stephen Paulus to write a piece for those instruments. Mrs. Hoeschler asked Mr. Paulus how much he charged, and he answered $100 a minute. “Well,” she told him, “it’s for our 15th anniversary, so how about 15 minutes?” He agreed, and eight months and $1,500 later, “Courtship Songs for a Summer’s Eve” was given its premiere at the Minnesota Club in St. Paul, during the course of a 40-minute private concert.

Last summer the couple celebrated their 38th anniversary. In the intervening years, the piece had taken on a life of its own and been recorded twice. The Hoeschlers still vividly recall its debut. “It was great fun,” Mr. Hoeschler, a lawyer, recently said from his home in St. Paul. “It was so much fun we decided to have him do the whole thing again five years later. Linda said the marriage isn’t so good that you can do it every year.”

That was just the beginning: they have since commissioned, in whole or in part, some 70 works, including, every five years, a new anniversary piece from Mr. Paulus. In fact it has become such a regular part of their lives that they’re beginning to sound a bit blasé. “It’s no big deal,” Mr. Hoeschler said, when asked about the logistics. “It’s really quite easy.”

Patronage of music by individuals may seem like a throwback to the days when noblemen maintained court orchestras with composers to write for them. Today, a few private donors have made names for themselves commissioning new music (notably Betty Freeman, who since the 1960’s has supported the likes of John Adams, Steve Reich, Morton Feldman and John Cage), but most of the big patrons of contemporary music are linked with institutions, giving money to symphony orchestras, operas and new concert halls.

As it turns out, anyone can commission a piece of music. Like the Hoeschlers, Maurice and Lillian Barbash were inspired to celebrate their 40th anniversary with music: they asked Yo-Yo Ma which composer he would like to write a cello concerto for him. He chose Leon Kirchner, and the piece went on to win a Grammy.

William Rubright, a professor of dentistry at the University of Iowa, befriended the Kronos Quartet over years of attending their performances. He made a major contribution toward Terry Riley’s “Sun Rings,” a multimedia piece for Kronos that had its premiere in 2002 and came to the Brooklyn Academy of Music in October.

Under its president, Heather Hitchens, Meet the Composer is trying to get the word out about private patronage. Recently, it published “An Individual’s Guide to Commissioning Music,” a compilation of articles about people who have done it, and how others can follow.

“A lot of people didn’t know this was something an individual could do,” Ms. Hitchens said. “They had a lot of misunderstandings about it. They had wild ideas about how expensive it would be.”

But lately, it seems, the message is beginning to be heard. Jennifer Basye Sander, a writer and editor in Sacramento, has ordered dozens of copies of the guide and is handing them out to everyone she knows.

“It sounds so lofty, so unapproachable,” said Ms. Basye Sander, who raised money in Sacramento to commission a new work from André Previn inspired by the works of the painter Wayne Thiebaud, another Sacramento citizen. The piece will have its premiere in April. “You think, ‘That’s what Austrian kings did.’ But it’s really not that hard,” Ms. Basye Sander said.

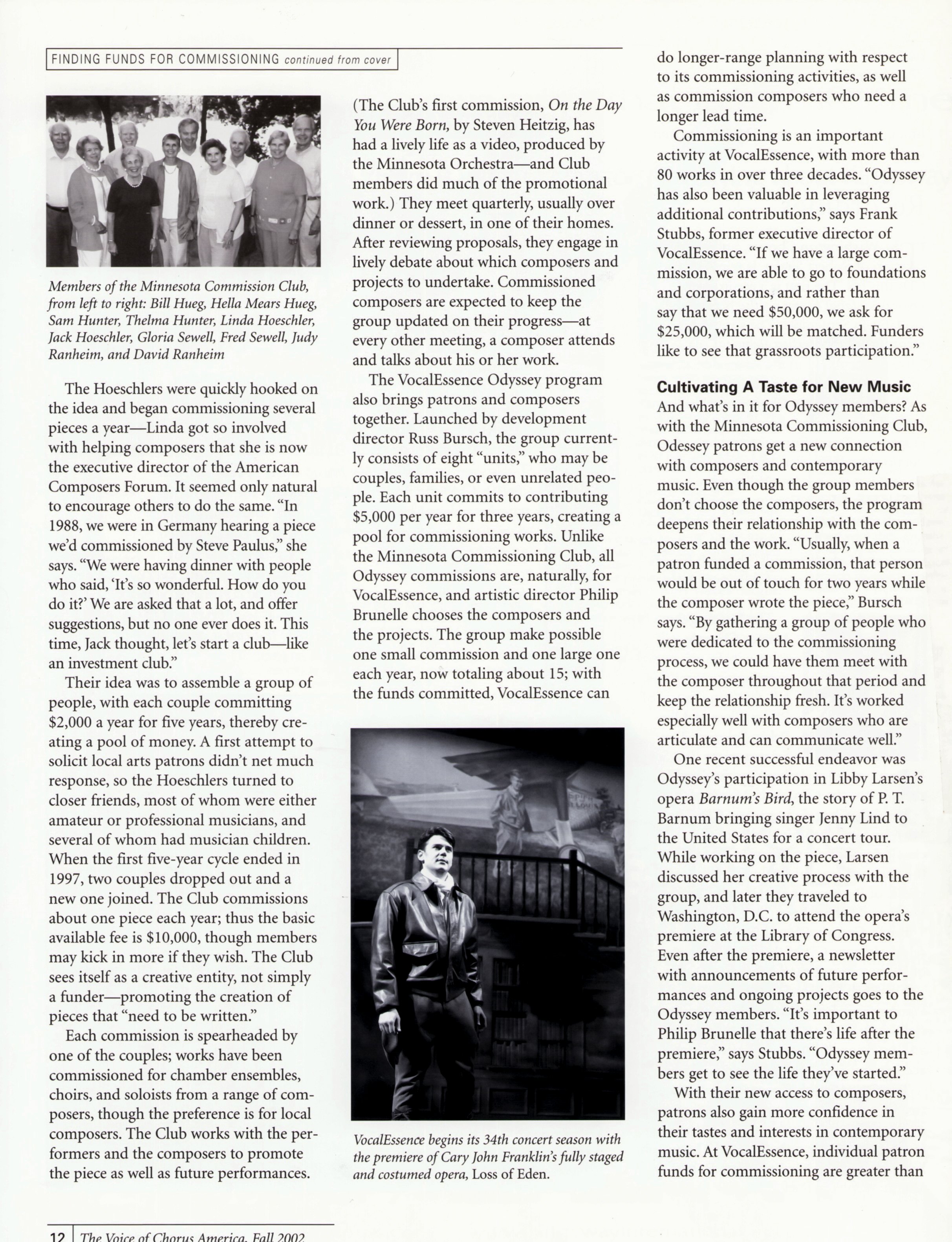

The Hoeschlers are walking advertisements for the joys of commissioning. Ten years and a dozen pieces after their first one, they formed a club, like an investment club, to share the fun of creating new works. Five couples each commit to giving $2,000 a year for five years.

The club has been going strong ever since, commissioning works that have been performed by the Minnesota Orchestra, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the choir of King’s College, Cambridge, and others. In June, they will fly to Potsdam, Germany, for their next premiere, “Slow Structures,” a chamber piece by Libby Larsen; and in September, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra is to perform a new piece written for them by Jennifer Higdon.

Kathryn Gould, a venture capitalist who lives in the Menlo Park area in California, had a different motivation: having heard a lot of new music that she didn’t like, she wanted to help create a repertory that she could enjoy. She plunged into commissioning with a vengeance. Her mammoth project, Magnum Opus, involves nine new orchestral works, each to be played by each of three San Francisco Bay Area orchestras. The next performance will be of Kenji Bunch’s “Lichtenstein Triptych,” performed by the Oakland East Bay Symphony on Feb. 25.

“I’m now one of the largest private patrons,” Ms. Gould, who also collects art, said recently. “That’s kind of hair-raising, considering that it’s not all that much money I’m putting into it. I haven’t added it all up, but all told, it’s probably about half a million dollars. I hope I can inspire people who have the means and the interest – and the patience, I might add.”

It’s an open field. You could buy paintings for years without approaching the level of leading art collectors. But individual music commissioners are currently being sought for some of the top musicians in the field. Midori and Vadim Repin, for instance, recently approached Meet the Composer to help them find patrons for four short works for solo violin. The works will cost $3,500 to $5,000.

“It’s a very different kind of commissioning,” Midori said in a recent telephone interview. “It’s intended specifically for uses in context: after a concerto as an encore, or in radio and television appearances. One reason I was prompted to do this is that often the day before a performance the local presenter says, ‘The local morning news called wondering if you would come make an appearance to talk about the concert, and they’d love it if you could play for a few minutes.’ How often can you play the few Bach pieces that would be appropriate?”

Of course, there’s a major difference between buying a painting by Modigliani and commissioning a piece for Midori. You can’t hang a piece for Midori on your wall. You don’t own the rights. It isn’t “yours.”

“At the end of the day, you have a few fun evenings and a CD,” Ms. Gould said. “When you collect paintings you have something that goes up in value. You can actually make money. What I do in music is strictly altruistic.”

Much of the time, you don’t even get a CD. The musicians’ union is notoriously strict about licensing recordings; musicians have to be properly paid for their performances, which means the cost of a professional-quality recording is often as much again as the cost of commissioning and performing a work in the first place.

Chrys Wu, a freelance writer in Los Angeles, contributed money toward a piece by Pierre Jalbert. Last year the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra gave the work its premiere. “It was phenomenal, especially the last movement,” Ms. Wu recalled. But she couldn’t get a recording of it. “I was like: ‘You don’t have to give me the whole thing. Just give me the last movement.’ “

Ms. Wu was part of Sound Investment, a commissioning club established by the orchestra as a way to generate new work. The club finances a new piece every year, giving members, who contribute as little as $250 a work, access to the composer and rehearsals at various stages in the composition process. This year’s commission, a piece by Donald Crockett, is to have its premiere on April 9 and 10.

“I didn’t know any composers willing to write for the amount I could spend,” Ms. Wu said. When she heard about Sound Investment, she added, “I got really excited, because it’s such a reasonable price, and you’re commissioning a symphony.”

She was not alone in liking Mr. Jalbert’s piece. After its first performance, enrollment in Sound Investment rose to 58 members from 36, only about half of whom are orchestra subscribers. Clubs are now springing up around the country.

If $250 is too much, there’s always Bang on a Can’s People’s Commissioning Fund, which you can join for as little as $5. Begun in 1999, it awards three commissions a year, and Bang on a Can presents them in a concert (this year, on Feb. 3, at Merkin Concert Hall).

“We started this fund,” said the composer David Lang, a founder of Bang on a Can, “because it seemed relatively easy to commission people who are successful, but if you want to invite composers who are on the fringe of our world – avant-garde rockers or performance artists or people who are too young to have any credentials – it is hard to find a funder. We thought that we could build a closer connection between these musicians and our audience, and expand the range of what we can accomplish.”

For people who want to go it alone, Meet the Composer is happy to work as a broker to suggest composers and ensembles to would-be patrons. One continuing project is a series of short works for flute and piano, organized by the flutist Marya Martin; there are still openings for donors willing to pay $3,500 to $5,000. Another is a series of commissions in memory of the murdered Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, set up by an anonymous donor who had seen the “Individual’s Guide.” One of the first pieces is being written by Steve Reich.

The Hoeschlers and their club have come to their own understanding of the commissioner’s role: they use their business experience to act as advocates for the composers they commission, for example, arranging for an orchestra to pay for copying the parts of a score (a not inconsiderable expense, and one the composer often has to swallow).

“We view ourselves as executive producers,” Mr. Hoeschler said. “Sometimes the orchestras need to be straightened up a bit: ‘Come on, you can do better than that.’ We’ll pay for the commission, but we want the orchestra to have some skin in the game.”

It’s also useful to remember that the first performance is only the beginning of the process. All too often, new works are played once or twice and then vanish from view. But an active patron can participate in the life of a commissioned piece for years. Mr. Hoeschler said the commissioning club’s next meeting will focus on a children’s piece by Steve Heitzeg and Debra Frasier, “On the Day You Were Born,” which had its premiere in 1995. It was later made into a DVD that has sold more than 20,000 copies.

“That piece has gotten played around any number of places,” Mr. Hoeschler said. “Now’s the time to give it another kick and keep that ball rolling down the road.”

The Pioneers Commissioning their own Classical Music Masterpieces

Patrons of classical music are upping the tempo by commissioning ambitious works to be performed live, recorded or broadcast for all to enjoy.

by Alex Marshall, Financial Times, June 7, 2018

For his 40th birthday, Richard Thomas, chief executive of pensions firm XPS Administration, was given an unexpected present: a season ticket to Wigmore Hall, the ornate Victorian concert hall in London’s Marylebone. He had been to classical concerts before – his grandfather took him to his first, a performance of Mahler’s Symphony No 5 at the Royal Festival Hall, when he was just eight (“We sat in a box and they brought us champagne in the interval,” he says). But he had long left that musical world behind for punk and reggae. Thomas couldn’t ignore the gift, though – it was from his wife – so he forced himself to go once a week.

“I hated it to begin with,” he says, sitting in a café near the Festival Hall. “I’d sit in the concerts thinking, ‘What the hell am I doing here? I can’t cope with these noises. They’re horrible.’ Then after about six months, I suddenly got it.” Now he admits to being something of a classical music“obsessive”, adding, “Whatever I become interested in, I tend to pursue it to its logical conclusion. So, for classical music, since becoming a concert pianist was never realistic, I began commissioning instead. And it’s been so much fun.”

Thomas is now arguably the UK’s foremost private individual who commissions classical music, akin to the patrons of old who supported composers from Mozart to Tchaikovsky. In 2009, he set up the Richard Thomas Foundation to commission works, currently totalling 15, ranging from preludes to an operatic duet, both from celebrated up-and-comers, such as British millennials Hannah Kendall and Charlotte Bray, to more established names, including Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson (who sadly died in February) and British composer Jonathan Dove. The Foundation was also one of the main co-commissioning parties of the 2012 Radiohead-inspired Radio Rewrite by American minimalist Steve Reich for the London Sinfonietta. Thomas often premieres works in the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room – when we meet, he’s translating some French poetry for his next concert’s programme. He has also created record labels Junk IBU and RTF Classical to ensure pieces are widely heard.

Unlike many classical music philanthropists, Thomas is intimately involved in each composer’s creative process. Others may donate to orchestras or concert halls – André Hoffmann, vice-chairman of pharmaceutical group Roche, for instance, funds Wigmore Hall’s new music programme – but Thomas invites composers he loves to tea at Soho House to talk ideas and new directions. “I once said to André, ‘You’re missing the fun bit!’ The fun bit isn’t writing the cheque; it’s sitting with the composer and being part of the creation.”

Thomas’s commissioning journey began with another milestone birthday. When he was nearing 50, he thought it would be fun to commission a piece for the party. “I used to buy a lot of art,” he says – his flat in Little Venice includes abstract works by German contemporary artist Thilo Heinzmann – “and if I liked somebody’s painting, I’d commission something. So why couldn’t I do that for music?” He had just fallen for some piano pieces by the minimalist composer Laurence Crane – “The most beautiful things I’d ever heard” – so asked his children’s piano teacher if he could arrange an introduction. Fortunately, the teacher was the acclaimed pianist Andrew Matthews-Owen, so soon Thomas and Crane were meeting in Soho House and discussing the project.

Crane ended up writing a 26-minute work for piano and string quartet, a piece that starts off as a waltz and quickly becomes, in Crane’s words, “a demented and rather leaden-footed folk dance”. It’s a stunning piece – if slightly unusual for a birthday – and it’s unsurprising to learn it’s been performed multiple times. It cost Thomas under £10,000 (a relative bargain, as top-rate composers like Crane normally charge around £1,000 per minute of music composed). “I suppose in the months leading up to the party, I was thinking, ‘This is all about me. Look how grand I am!’” Thomas says, with a smile. “But the more it went on, the more I ended up finding pleasure in being able to help Laurence create something he otherwise wouldn’t have done. I just wanted to do it again.”

Back in the 1700s, private commissions were classical music’s lifeblood. But such patronage dropped away in the 1900s with the rise of professional orchestras, who commissioned music themselves, and music publishers, who tried to control the process. Some individuals still came to the fore, such as Sergei Diaghilev, founder of Paris’s Ballets Russes, who commissioned Igor Stravinsky’s great works, including The Rite of Spring (the premiere of which was underwritten by Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel). More recently, Betty Freeman – “a modern-day Medici” according to The New York Times – used her inheritance to support every composer who took her fancy, until her death in 2009. She saved avant-garde composer Harry Partch from a life on the streets and gave experimental pioneer John Cage an annual grant to do with as he pleased. Minimalist John Adams dedicated his acclaimed opera Nixon in China to her.

Today, Freeman’s role in the US has arguably been taken by Justus Schlichting and his wife Elizabeth. Schlichting, a childhood trombonist and more recent cellist (“Professional cellists look at me with wonderment and horror,” he says) sold his healthcare financial services company, S&S Datalink, in 2011. He expected to spend his retirement in Laguna Beach doing “costly sports” – sailing, flying – but had a change of heart after a performance of Beethoven’s “Razumovsky” string quartets. “I was sitting there having an incredibly emotional response to the musicand realised someone back then had made it all possible – this Razumovsky. And I suddenly thought, ‘I don’t know who he was.’ It turned out he was just fascinating.”

Andrey Razumovsky, born in Ukraine in 1752, had no particularly special standing as a young man, but managed to talk himself into the Tsar’s good graces – “The Tsarina’s at least,” says Schlichting – and rose to become Russia’s diplomatic representative to Vienna. There, he employed a house string quartet, for whom he commissioned Beethoven to write three pieces in 1806. His story inspired Schlichting to begin commissioning himself, with the aim of financing at least one piece that might be enjoyed by music lovers for as many centuries as a Razumovsky quartet. “I just had this realisation, ‘I want to be Razumovsky!’” says Schlichting. Since 2012, the Schlichtings have commissioned about 30 pieces a year, at an average of $9,000 per work – the most costing $65,000 for a work performed by the LA Philharmonic.

The Schlichtings’ scale of involvement is wide. Often they give a composer free rein to write their dream piece and don’t even set a deadline. Once the couple gave violinist Jennifer Koh funds to help repay the loan she had taken out to buy her Stradivarius, in return for a set of capriccios written by her friends, who are significant composers. Sometimes they seek composers out, other times composers call them, and Schlichting adds that donating to arts organisation New Music USA has helped facilitate the process. He is a member of its New Music Connect group, which gives him access to artists’ grant requests. “If I see something that excites me, I claim it.” Schlichting’s advice to anyone who wants to follow his lead is simple: “Remember that every new piece requires three things: somebody to write the music, somebody to play it and somebody to present it. If you don’t have all three, it’s not going to happen. A composer doesn’t want to spend time and energy writing a piece, no matter what they are paid, unless they know it’s going to be performed.”

Schlichting admits commissioning can be rocky at times – slipped deadlines are common and people can have unfathomable propositions (he once underwrote an opera, Hopscotch, that was set in 24 limousines driving around Los Angeles; it somehow ended up being a success) – but when he shares all his stories, it’s obvious he enjoys the challenges as much as the end result. “We tried for children, and alas…” he says at one point. “But in reality we consider all the young composers our kids.”

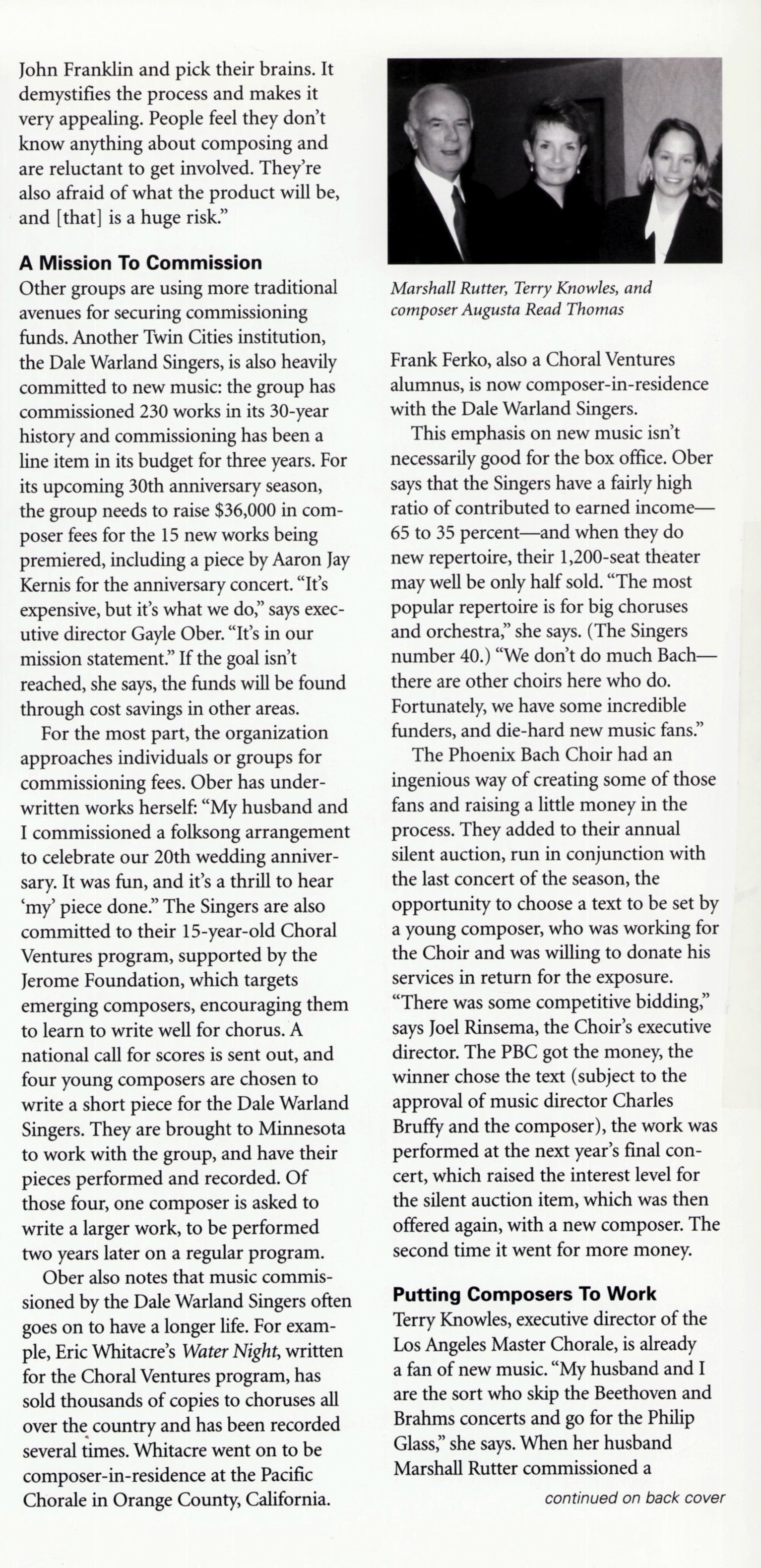

A more financially accessible way to commission a symphony is to join an orchestra’s commissioning club. Birmingham Contemporary Music Group’s Sound Investment scheme, for instance, invites music lovers to contribute towards specific pieces from as little as £150, for which they are thanked with the opportunity to attend rehearsals or an introduction to the composer. But more active involvement can come from privately formed clubs, such as the Minnesota Commissioning Club, set up by new music enthusiasts Linda and Jack Hoeschler. In 1990, the Hoeschlers (who attended John Cage “happenings” in the 1960s) had commissioned a few works themselves and wanted others to “join in the fun”. So they invited four couples to each contribute $2,000 a year for five years to commission new works and arrange multiple performances. The collective has inspired other clubs and is still going strong; its major works include a carol performed during the celebrated Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols at King’s College, Cambridge, which is broadcast in the UK on BBC TV and radio, and in the US on over 300 local radio stations.

Linda Hoeschler says key to the collective’s success was finding people who not only love classical music, but have opinions about it and can debate ideas. It also helps that club members accept the risks involved – for example, not getting a masterwork every time. “Once, I was having a dinner party at our summer house; I had the radio on in the background and a piece of music was playing. I said to the table, ‘That is exactly why people hate new music.’ Of course, the presenter then said, ‘Commissioned by Jack and Linda Hoeschler.’”

Linda has few mementoes of commissions aside from signed copies of the scores, but musicians who have worked with her and her husband regularly ask if they can rehearse at their house, and such performances have turned their home into a true musical sanctuary. “That’s been one of the greatest gifts of my life,” says Linda.

A further way to begin commissioning is to use a broker. Ed McKeon of London’s Third Ear has arranged pieces for clients, including the financier Anthony Bolton (a major donor to a host of classical music institutions and a composer himself) and Esther Cavett, a former partner at Clifford Chance. McKeon is an evangelist for private commissioning, whether it’s someone looking for a birthday gift for their flute-playing daughter or a celebration for their wedding anniversary. Expect to pay a minimum of £1,500, he says, with a full-scale opera upwards of six figures. “Commissioning gives you an experience, a narrative,” he says. “When you commission a piece of classical music it can be intimate or it can be vast and public. If you can embrace that range of possibilities, then the rewards are extraordinary.”

Back outside the Royal Festival Hall, I ask Richard Thomas about all the extraordinary experiences he must have had commissioning, but it’s hard to get him to talk about the past. Instead, he starts talking excitedly about Joseph Phibbs, a British composer he wants to write a lied (one problem: Phibbs doesn’t speak German). There’s also a work he’s planning with the much hyped cellist and composer Oliver Coates. “And I really want to commission Dobrinka Tabakova,” he says. “Her music is amazing. It’s informed by folk music from eastern Europe, but it couldn’t have existed before now. I keep telling her, ‘Just write a little cello solo or something for me.’”

He pauses for a moment. “Obviously, by talking to you about my passion, I’d like to inspire more people to begin commissioning works,” he says. “There’s so much incredible music that needs to be written. But could you also maybe make the piece a plea to Dobrinka? I’d love her to accept that commission…”