Awards and Salutes

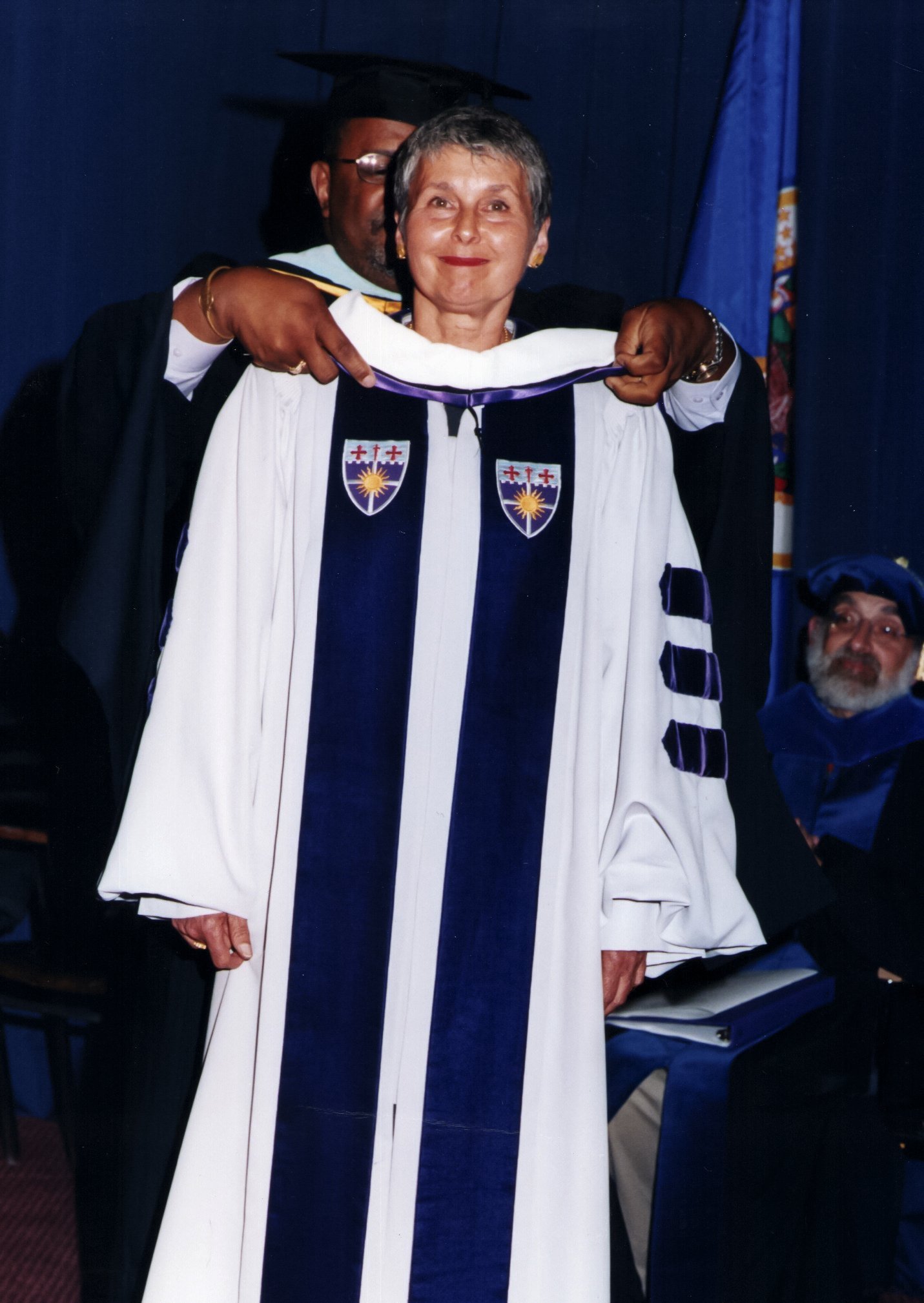

The University of St. Thomas today [July 5, 2003] honors with its degree doctor of humane letters, honoris causa

Linda Hoeschler, in a St. Thomas magazine profile several years ago, you recalled of your childhood: "I never felt limited…My parents made it clear I was responsible for my own well-being." In the years since then, you have approached each of your roles - as business person, community servant, wife and mother - with a similar clarity, sparked by boundless energy and creativity and tempered, above all, by profound integrity and generosity.

Growing up in New York, you had forward-thinking parents who encouraged your career aspirations, stressed achievement and inspired dreams. Your father, a circulation director for a chain of newspapers, took you to work with him and introduced you to women in business, medicine and law. By the age of 7, you were reviewing children's columns for the newspaper chain. "I was always taken seriously," you said. "My opinion was valued.

Your education gave you even more opportunities to hone your intellectual skills. At Trinity College in Washington, D.C., and then at Barnard College in the early '60s, you majored in government, economics and Russian studies.

You made scholarship your first priority, graduating with honors and earning a Herbert Lehman Fellowship at the New School University. There you received your master of arts degree with highest honors.

In 1966 you married attorney John Hoeschler.

You and Jack were blessed with two children, Kristen and Frederick.

You began your career as a mother with young children, first as a writer, editor and arts critic in the Twin Cities, then as director of the Minnesota Governor's Commission on the Arts. You then began a successful 15-year career in Minnesota's corporate community.

You became the first communications staffer to be named a corporate vice president at Dayton Hudson Corporation. Next, as group vice president of National Computer Systems, you contributed to the significant growth of that company.

In 1991 you were president of Landmark Investors Ltd., a consulting firm, when the Minnesota Composers Forum, a small nonprofit organization, sought your leadership amid major challenges of organizational and financial disarray.

Although you had been involved locally in the arts for more than two decades, you considered your expertise in business and marketing. The Forum persisted. A longtime devotee of the arts, you said, "I felt this was too important an organization to fail." You agreed to lead the Forum for a year, rolled up your sleeves and got to work.

And the music played on.

Melding your love of music with your considerable business acumen, you reinvigorated this arts organization into one of the most respected in the United States. Since 1991, the forum has established a network of chapters stretching across the country and in 1996 renamed itself the American Composers Forum. Its ranks of member composers, performers, presenters and organizations grew from 400 to 1,700. Its two-year nationwide commissioning project,

Continental Harmony, was a centerpiece of the National Endowment for the Arts' high-profile Millennium Project. A release by its new-music record label, Innova, received a Grammy nomination. The forum's budget grew from barely $300,000 in 1991 to nearly $3 million in 2003. Today this organization nurtures composers and communities in all 50 states through educational and residency programs, a radio show and commissioning programs.

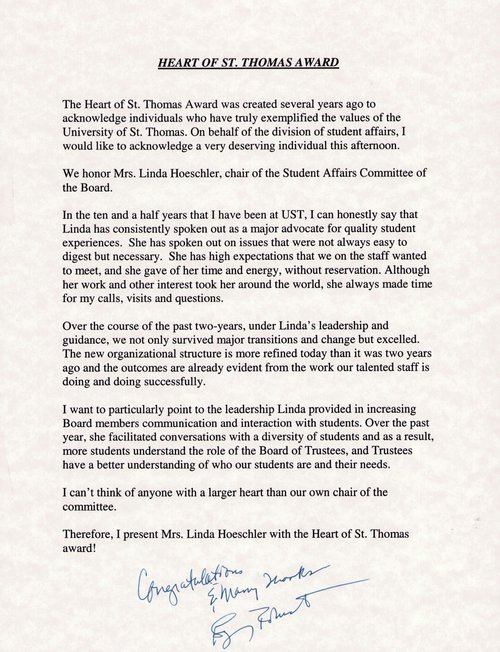

You also have given your time so generously to a host of arts, business, charitable and educational boards, including the University of St. Thomas board of trustees, which you joined more than a decade ago. Acknowledging your leadership of the board's Student Affairs Committee, St. Thomas Vice President for Student Affairs Gregory Roberts recently presented you with a Heart of St. Thomas Award given to those who truly exemplify the values of the university.

Today, as you celebrate your recent retirement from a 12-year tenure as executive director of the American Composers Forum, you have a reputation, in the words of one newspaper reporter, as "a new-music fix-it diva."

We prefer to quote Minnesota composer Steve Heitzeg, whose 1993-94 residency at St. Thomas was supported by the Minnesota Composers Forum:

"Linda lit a fire of musical inspiration and creativity across this country."

May that fire - and your many others - continue to burn brightly as we offer hearty congratulations and best wishes and confer upon you the degree, doctor of humane letters, honoris causa.

University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, MN: Commencement Speech-July 25, 2003

Thank you for the double honors you are awarding me today: first the honorary degree, and perhaps more thrilling, the opportunity to speak to you students I sincerely applaud each of you for your diligent work securing your degree-this sheepskin is proof positive of your devotion to learning and self-improvement. And as one who received a master's degree, but lacked the fortitude to pursue my PhD, I am particularly in awe of the newly minted doctors in this audience.

I am most grateful to St. Thomas for honoring my work today, both that done at the American Composers Forum on behalf of the composers and communities of America, and that offered as a Board member of St. Thomas.

My service to St. Thomas has been, in fact, more the reverse: St. Thomas has served me richly in terms of intellectual and spiritual growth. Over the past decade I have had the most wonderful opportunities here to work with and learn from exceptional people, particularly the students. While it may sound insincere to state you love and care about an ever-changing group, the students of St. Thomas have compelled my mind, and won my heart, forever.

As you leave this campus and go forward in life, I truly hope your appreciation and admiration of St. Thomas grows, and that you, in turn, make personal sacrifices to support its students and its work.

I presume that each of you has a plan, whether vague or well-defined, outlining what you'd like to do with your newly garnered degree. I am going to ask you to put that plan aside, at least for the duration of my speech. For each of you suspects, I am sure, that whatever endeavor you've trained for today, will probably radically change within 10 years. The job you covet now may not even exist ten years from now, at least in the same form. You might not even want that job, anyway.

Instead of remaining anchored to your current plan, which may only lead to disappointment and frustration, I would like to suggest a more fluid way to approach the rest of your life. All you need are three things: a focus on your personal values, the mind of a baby, and the eyes of an immigrant. I'm going to talk about these in reverse order.

Lately I've been doing a lot of personal genealogical research. What astonishes me, over and over, are the incredible stories of our immigrating ancestors. None of mine were famous or persons of notable achievement, but despite that, all were inspirational models.

When faced with poverty, poor education, lack of English, discrimination and other seemingly endless challenges, my settling ancestors, and yours, fundamentally found America to be a place of unceasing opportunity.

Each had more than enough reasons to inspire 10 lifetimes of depression, especially those who came here unwillingly. Instead, they figured out how to make America work for them. They made things, they started small enterprises, many of which failed, only to re invent others. They homesteaded land and sometimes lost it.

Well, that was then, and this is now, so you may think. Life today is more complicated and demanding. Our cities are more crime ridden and less community oriented. But is there less opportunity?

Look at the immigrants around us, some certainly in this class of graduates. They start with the menial jobs, the ones that are "below us", and somehow manage to send money back home. Some fail, of course, but for the most part, each of us should try to catch a case of their enthusiasm!

I am truly amazed at the more recent Twin Cities immigrants, the Hmongs and Africans, who think this a great place to live, despite our harsh winters. These tropical emigrants express gratitude for the ability to work at all. Moreover, they all seem to have plans for the future: ideas and openings you and I would overlook. (Just the other day I called a Russian-born accordionist to play at a party, and he offered to clean my house and office.)

I urge each of us to consistently look at our communities, jobs and families with eyes that behold opportunities galore, not insurmountable barriers. The eyes of the immigrant.

About 20 years ago I read an article that continues to intrigue me. The journal of the Bell Museum at the University of Minnesota posed the question, "Why does nature make babies?" The writer detailed the substantial drawbacks of babies: almost no infant on earth is born self-sufficient or able to defend itself. Most reptile and mammal parents need to feed, groom and train their babies for lengthy times. Babies are clearly a poor means to continue each species.

Or are they? In physical terms, babies may be inefficient. But the genius of babies lies in another realm, lack of memory. Because babies have no memory, they are far more adaptable than their progenitors. Instead of being confounded by changes, babies grow up devising ways to adapt, ways often impossible for their parents.

To think that all my life I've believed and, in turn preached, that those of us who forget history are condemned to repeat it. While there is truth there, consider the flip side of this maxim. At what point does our history cripple our ability to adapt to change?

How often do we resist a person, idea or situation because of past negative experiences? Consider how much more empowered we would be if we approached previously distasteful situations or people as the first encounter. Like a baby, we would not only be open to the person or setting, we would try to discern how they could entertain or help us.

Babies are optimistic, curious, self-centered and unprejudiced. Each of us would do well to approach personal hurdles created by past experiences with a newborn's mind, unhampered by memory. Lack of memory can be a very good thing, a really comforting thought at my age, and a possibly galvanizing idea at your age. The mind of a baby.

Now for the most critical idea that I'd like you to consider, the structuring of your lifearound your personal values, not around material expectations, nor around goals that others have suggested. You have sole custody of your entire life, so why not craft it around matters that fascinate and compel you?

I urge each of you today, or within a week, to write down your values regarding your family, community, work, spirit, health, recreation etc. What are the core beliefs that reflect your soul? Then write down a parallel list of your current activities. Do the sum of your activities realize your key values? Probably not, because most of us confuse our work resume with a meaningful life.

Starting today, shape your life's activities-your job, your family, your reading, your volunteer commitments-around your core beliefs. These beliefs, by the way, will change little as you age, so they can guide you better than any current career plan. I also suggest that whenever external changes disorient you, just revisit your list of internal values for comfort and for guidance. These are your eternal truths.

You will do your best work and make your most significant contributions if you know that you are spending your time on things important to you. Moreover, you will never need to advertise, explain or argue your beliefs, because your life will be your message. A focus on values.

I wish each of you joy and passion, and hope you consider my modest ideas: shaping the rest of your life around your personal values, and living it with the accepting, open mind of a baby, and the wonder-filled eyes of an immigrant. Thank you.

University of Maryland Music School, Commencement Speech

By Linda L. Hoeschler, May 22, 2005

Thank you for that warm introduction and for the exciting honor of speaking to you today. I feel like a poseur lecturing music graduates of talent and accomplishment, particularly since my piano playing has deteriorated from just decent to really lousy. Moreover, my early career’s work as a music critic produced recurrent nightmares in which the orchestral conductor didn’t show up, and the first violinist would point to me and shout: “If you’re so smart, you take the podium and conduct us!” So much for my dreams of great music making!

But despite my personal failings and anxieties in this art, I did go on, throughout and after a fairly successful corporate career, to stay involved in music: as a choral singer, writer, commissioner of music, and head of the now-largest composer organization in the world, the American Composers Forum. Music, particularly new music, has been one of the most powerful through lines of my life, offering me some of my greatest joys, profound comforts, enduring friendships and intellectual challenges. It is from these experiences and with this passion that I speak to you graduates today.

I am sure that all of you have and will receive warm congratulations on your graduation, often coupled with the question: “Now tell me, what will you do with your degree?” I suggest that you counter with this question: “Are you speaking about my music degree vis a vis my career, or my life or in society?” My career, my life, or in society. I’d like to offer some ideas regarding each, taking them in reverse order.

Our society today is permeated by passive music experiences, with wallpaper surround sound, buttons in the ear, iPods on every desk. John Cage’s composition, “4’33””-- all of it silence-- now seems more like music than the tonal noise that chronically assaults us. Music, once the apotheosis of man’s spirit, is now in danger of numbing our souls, as we tire of its constant presence or hear it blasting women and glorifying violence. Depressing, yes. Irreversible, no.

Your role in society as musicians lies in your ability to make music: music as activity, not passivity. Share that ability. Your innate artistic talent, coupled with focus and discipline, has made you the musician you are today, a craftsman who can write, teach and perform music. You can do more than simply use your honed musical gift for your personal enjoyment and development. You can match your technical skills with an activist’s passion to help shape and enlighten our society. Teach us all how to become active participants, whether as your students, your friends and family, or your audience.

I urge you to do what artists do best: lend us your extraordinary ears, your eyes, your mind to interpret a composition, an idea, the world, in new and thoughtful ways. That means much more than just sitting down and playing a piece.

I commend you first to continue to educate yourselves, not just in music, but in the ideas and events of history and of today. Read books and periodicals, attend lectures. Too often we in the arts only offer emotion, not compelling reasons, in proposing or defending, say, the role of arts in education. We often lack data or thoughtful analysis. We crumble and maybe even apologize for our primarily intuitive opinions when strongly challenged.

But when you are grounded in a sense of how the world we live in came to be, you can approach your classroom or concert hall with a greater context for your work, and a higher sense of purpose. In your lesson, programming or composition, tell us how this old or new work fits into our culture, and how and what we should listen for.

Find the Leonard Bernstein, Kenneth Clark, and Joseph Campbell in you: the scholar and the evangelist. Elevate us, amuse us, challenge us.

Remind us of the painful brevity of our lives, and that music, the most evanescent of the arts, can give us enduring insights and beauty. Help us see and hear the world through your senses. You can make this a more uplifting, less passive world, but you must be committed to do so. You don’t always have to be great, but you should always be compelling. So please lend us, your friends and countrymen, your ears, and help create a society brimming with active music participants.

Now for the role of your music degree in your life. First of all, never equate your paid work with your life. As Gandhi said, your life is your message, not your jobs, your awards or your possessions. You probably all hope to get full-time jobs in music, and many of you will. For others, music will be a part-time vocation, often complemented by other employment. Seeing your musical life within the context of your entire life can reduce work-seeking panic. In fact, I think it is the only way to view the import of today’s degree.

To understand where music fits within your life, I suggest that after the graduation festivities die, you write down a list of all your values: your values regarding your art, family, community, work, spirit, health, recreation, etc. Then write down a parallel list of your current activities. Do the sum of your activities realize your key values? Probably not, because most of us confuse our work resume with a meaningful life.

Remember, you have sole custody of your entire life, and that is the only fact that distinguishes you from all the thousands of music students graduating around the country this year. So why not craft a life around matters that fascinate and compel you? Music and your music career are only part of that equation.

Starting today, shape your life’s activities—your job, your family, your reading, your volunteer commitments—around your core beliefs. These beliefs, by the way, will change little as you age, so they can guide you better than any current career plan. These are your personal eternal truths.

You will do your best work and make your most significant contributions if you know that you are spending your time on things important to you. Moreover, if you fail in one area, you will have the counterbalancing support of your other values being realized.

Since I have the podium, I will urge one value for each of you life-managers to consider: the building of a music community. Because of a scarcity of jobs and performance opportunities, artists are in competition with each other. But that external condition doesn’t necessarily negate the construction of internal support.

The best artists I know are the most generous artists. They are fair in evaluating their peers, they attend each other’s performances, and they offer help when asked. Sure, they worry about their careers, but they don’t let that get in the way of building community. Are they generous because they are already successful and can afford the largesse? Could be, but I don’t think so. All I know is that they tell me they have never regretted a single act of kindness or a sacrifice to help another. They have been more than rewarded by good deeds that come their way. It’s not true that what goes round, just comes round. What goes round comes back in multiples.

Now for the most obvious answer to the question of what you are going to do with your music degree: a job, a career in music. Well, congratulations, but I would say to you that you are not entering a career in music, you are taking on the joint jobs of sole proprietor and educator. You are moving out of the predictable framework of academia into one of the most entrepreneurial fields today. You are about to launch your own enterprise.

Even if you secure a job in a school, ensemble or orchestra, you are going to have to keep promoting yourself as a musician, if you want to perform or compose on the side. A couple of courses in marketing and accounting may help, but there are many more things you can do to launch and maintain your career, your enterprise in music, whether or not it is your fulltime occupation. You need to develop patronage.

Let me take myself as an example. In 1980 my husband and I decided to commission a piece of music for our 15th wedding anniversary. We thought this would be a single event, a one-time endeavor. We asked Stephen Paulus, a Saint Paul composer whom I had met through some prior work, to write a chamber piece. From the beginning, Stephen deftly engaged us in deciding on the instrumentation, length and text. He periodically invited us to his home to play through the music as it developed. He not only educated us in the art of commissioning, he made it exciting, uplifting and joyful.

And what is the result today? My husband and I, now approaching our 40th anniversary, have commissioned over 70 new works of music. 15 years ago we launched a Commissioning Club to introduce 5 other couples to the fun of commissioning. That Club continues to thrive, and is the model for other such clubs around the country. With Stephen Paulus’ help, we are helping cultivate a better environment for the composers and performers of today’s new music, because he made the effort to train us how to become good commissioners, good patrons.

Dominick Argento is a very successful Minneapolis composer who has won the Pulitzer and multiple other prizes. A few years ago he told me that his career was going nowhere until Elisabeth Soderstrom fell in love with his music, and asked him to write more works for her. Dominick was at least 50 when that happened. When composers would come to me at the American Composers Forum, asking for career advice, I always told them about Dominick’s experience and suggested that they, too, should find the person or ensemble who loves their music, then write music for them. Don’t think you always need to find new performers or a new audience. Remember to cultivate your existing fans.

A few weeks ago in New York, I had breakfast with a friend who runs a national music performers organization. We were talking about the art of developing patrons, and he told me a story. About a year ago he ran into an old friend who introduced him to a young pianist at his side. The pianist took my friend’s card and began sending him periodic emails about performances, competitions, with sound clips. My friend said that a few months later he was called for the name of a substitute pianist. Guess whose name he suggested. My friend had become his patron.

Each of us has a personal work style. It doesn’t really matter whether or not you’re an introvert or extrovert, whether or not you’re more comfortable writing someone or talking to them in person. If you learn to look for connections, for opportunities, for patrons, you can make a good to great career for yourself. If you peg your career success on competitions, reviews and recordings, you will drive yourself crazy when you slip or don’t get the recognition you think you deserve.

Just as I’ve urged you to actively create a life for yourself, with your work in music as a subset, so must you fashion a career using your wits, opportunities and enthusiasms. If you are a great artist, you will rise to the top fairly easily and quickly. But, in fact, the world of music primarily comprises craftsman-like performers and composers, who offer us equally valuable, if less startling gifts, as teachers, inventors and players. They compose the world I primarily know and support, mostly with a lot of listening and a little advice.

Most of the successful musicians, and they have each defined what they consider success to be, have found a person or organization who believes in and encourages them—and not just their mothers! They have succeeded, perhaps more modestly than they originally dreamed, but often with a great sense of worth and knowledge of how they enrich this world.

Please know that there are many potential patrons who don’t want to merely buy the piece of art that hangs on the gallery wall. We want to know you, to support you, to be educated and engaged by you. We are not always obvious, but we are pervasive. Take hope, for in this world of disposable goods, many of us do not create, but are looking to attach ourselves to those who do. Look around, send out the feelers, and together we can work to help build or augment your career.

And so, my friends, congratulations on this culminating recognition of your innate talents coupled with a lot of hard work. Thank you for considering my modest ideas about the worth of your degree in your career, your life and in society. As activists in each arena, you have important, edifying gifts to offer. I look forward to noting your achievements and to cheering you on from the sidelines. Thank you.

Honorary Degrees and Commencement Speeches

Doctor of Humane Letters

Honoris Causa

to Linda Hoeschler

St. John’s University, Collegeville, MN

Wielding an unusual and powerful combination of energy, business savvy gained from a successful career in several major corporations and devotion to the music arts, you, Linda Hoeschler, have steered the American Composers Forum to national prominence, fostering the growth of audiences for new music across the country and reaching composers and communities in every state.

A radio show, a record label for new artists and composer seminars initiated by the American Composers Forum reach out to nurture artists and audiences nationwide. Visionary music residency and educational programs, launched under your leadership, help people of all ages, in communities of all kinds, discover that new music can sing for them, that composers can create original works that help express their yearnings or heal their wounds or celebrate their joys. From elementary school classrooms to middle school rehearsal rooms, from church halls to city halls, the Forum has become a dynamic agent for music education.

Your commitment to community is not only expressed through your creative leadership at the American Composers Forum. You have also generously shared your gifts through service on numerous nonprofit boards, including the University of St. Thomas, Chamber Music America, the U.S. Delegation for Friendship Among Women and the Northwest Area Foundation.

For your vision, your generosity, and, above all, for providing composers with audiences they did not know how to find and audiences with composers they did not how to look for, Saint John’s recognizes you with gratitude and confers upon you:

The Doctor of Humane Letters

honoris causa

on this eleventh day of May, two thousand and three.

Dietrich Reinhart, OSB, President

Degree Response

By Linda Hoeschler, May 8, 2003

Thank you. I gratefully accept this honor, especially meaningful since it is given by an Institution that is so deeply committed to art and culture, to the creation and preservation of the best art of our times, and of times past.

I was delighted and astonished by Brother Dietrich’s letter inviting me to receive this recognition, particularly since those of us who lead cultural organizations are seldom public figures. Our best work is unseen—the promotion of artists, the cultivation of audiences, and the begging of funds to do so.

Thank you also for this tribute to the accomplishments of the American Composers Forum. Still, these achievements are not really ours to claim. They are the achievements of thousands of composers who dared to embrace new ideas, and of hundreds of thousands of people, like you, who gave these artists a chance to show that composers have a critical role in celebrating and healing our communities—all with and for a song.

On your day of commencement, the beginning of the next phase of your life, I offer you my warmest congratulations. But as a mother, on Mother’s Day, I cannot resist offering some advice.

I urge each of you to articulate, to write down your values, the things and issues you really care about. Then shape your life’s activities—your job, your family, your volunteer commitments—around those core beliefs. You will do your best work and make your most significant contributions if you know that you are spending your time on things important to you. You need not advertise or argue your beliefs if you live this kind of life, because your life will be your message.