A Perspective on North Korea

By Linda L. Hoeschler, December 10, 2008

Thank you for inviting me to speak to this astute and curious group. By way of disclaimer, I admit that I am not an expert on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or DPRK, the official name of North Korea. My observations today are based on some coursework, extensive readings, and a week-long trip I took last April with the Delegation for Friendship Among Women. In fact, in preparation for this talk, and feeling very much the novice, I wrote everyone I knew who had spent a lot of time in the DPRK. They each told me the same thing: don’t worry, no one really knows what’s going on in North Korea.

The Delegation is a group with whom I travel every year or two to a developing area of the world. The goal of our Delegation trips is to meet female leaders, gain an understanding of their issues, exchange ideas, and offer them an informal network of contacts in this country. On many trips, we have made significant friendships and helped women leaders, since we try to bypass government bureaucrats in conveying information and assistance. I will confess now that I doubt if we can ever have such an impact on the DPRK.

Today I’d like to give you an overview of the DPRK by covering several areas:

Western visitor travel in the DPRK;

the North Korean view of America and the Korean War;

the US view of the DPRK according to our embassy in Seoul;

the role of non governmental organizations, or NGO’s and Korean Americans in providing relief aid;

problems affecting Koreans today;

signs of economic change;

music and the visit by the NY Philharmonic;

and the cult of personality of the great and dear leaders, Kim Il Sung, and Kim Jong Il.

To set the proverbial stage, I caution you that while North Korea is every bit as strange and repressive as you think, it is also surprisingly different: visually appealing and quite lovely in many ways. In fact, I think we were all surprised at the attractive appearance of Pyongyang, the capital, and the tidy and nicely landscaped public areas in the villages. The DPRK is a mix of contrasts, which in turn provoke a mix of emotions. The one constant emotion, however, was frustration, because you never really know what lies beneath the surface of what you are seeing (or hearing)!

That frustration ties into my first topic, visitor travel in the DPRK. Isolation and control are keywords here. Pleasant agreement with your requests, then not fulfilling them, is another hallmark. Surrender to the system is the only way to begin to enjoy your trip there.

This presumes that you can get into North Korea to begin with. Since the United States has no formal relations with the DPRK, a North Korean agency must invite you to come. This agency is responsible for your appointments and wellbeing when you are in the DPRK, a not insignificant task since each tourist group, usually no more than 8 persons, has 3 North Korean “minders” at all times. Our Delegation for Friendship worked through Global Exchange, a San Francisco travel agency whose trips focus on human rights. Global Exchange, in turn, had recruited a Mrs. Hwa Young Lee, a South Korean-born US citizen who is devoted to the reunification of the two Koreas; therefore, Mrs. Lee had DPRK contacts and asked the Korean Committee for Solidarity with World People to issue our invitation.

What followed was a series of fits and starts in terms of being allowed entry. I will not bore you with the details, but despite our finally being approved by the North Korean delegation at the UN, we did not have our final visas for entry until we were already in China. It was clearly an act of faith on our part, when we boarded our US planes for Asia, that we would be allowed to go to the DPRK.

On April 9th in Shenyang, China we boarded Koryo Airlines, the national airline of North Korea, for Pyongyang, the DPRK capital. Some of our group had previously dropped out of the trip because Koryo Air, comprising old Russian Ilyushin and Tupolov jets, has an unsafe rating and several airports deny it landing privileges.

When we landed at the small, retro Pyongyang Airport, I was initially comforted by an attractive fleet of Koryo planes on the tarmac. Only later did I learn that these freshly-painted planes don’t fly and are missing many of their innards, having been cannibalized for repair parts for the few operating planes. By the way, I learned this summer that Air Koryo just purchased a new Tupolov, since China finally forbade landing the old Koryo clunkers in Beijing for safety reasons.

The airport security agents scrutinized our visas and passports, and noted our lists of belongings lest we leave anything there. They also took our cell phones, but allowed us to keep our digital cameras with short video capability. Since the lists of items that tourists can bring shifts constantly, we were unsure what we could keep until we left the airport.

Our pleasant guides or minders loaded us on a mini bus and took us to the Koryo Hotel. Except that shortly before we left for the DPRK, our hotel reservations had been changed to the Yanggado Hotel, also in downtown Pyongyang. But on the route into the big city, we pulled into the driveway of a mansion that I presumed was a government office for our guides. But no, it was the Kobangsan Guest House, in all its isolated splendor. Mr. Kim, our genial lead guide, told us that the Korean Committee for Solidarity had decided to put us there because we were “so old.” So much for initial diplomacy!

Our guest house was most spacious, with large rooms, beds almost as hard as the floor, and Soviet-era decorations. The TV in our room showed three stations, a truncated version of CNN news, a North Korean channel and a German/Italian chanel. The hotel food was very good and creative, as it was throughout the whole trip. But no one else stayed at the guest house, except for our guides and a skeleton hotel staff.

This rather splendid isolation was a hallmark of our entire trip, and prevented us from ever being able to have any private conversations with any North Koreans. I would add that although I am always careful in any totalitarian country, because the errant quoting of a native might get that person thrown in jail, there was no need to be careful here because there was no chance to be alone with any local.

In terms of agenda, the three guides worked hard to keep us busy and interested, but we soon realized that they had a set menu of items they could offer. And no more. The guides would say they would look into requests for itinerary changes, but if your choice wasn’t on the menu, there wasn’t a chance.

For instance, we primarily wanted to delve into women’s issues, but were only allowed to meet with the Korean Democratic Women’s Union, a Communist party entity, much like those found in the former Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. During our very cordial meeting with the female leaders, there was no exchange of ideas, because the North Korean women kept claiming that they had “no problems.” What about spousal abuse? A puzzled look and reply: “I guess the community would handle it.” And so it went with every issue we tried to discuss. They were always “on message” and our Delegation has never had more frustrating meetings with women in any country.

I also informed our guides that I had a St. Paul friend, Young Nam Kim, a violinist who was in the DPRK at the same time. I told the guides that Young Nam would be looking for me at our original hotel and I’d like to see him. Although our minders were very pleasant, there was no attempt to reach Young Nam—the guides kept smiling and telling me I’d see him at the final concert (which I didn’t!). One time I began conversing with a French woman who worked for an NGO and lived in Pyongyang. The guides kept trying to pull me away, insisting they couldn’t continue the tour of a very contained flower exhibit until I came along, too. She clearly wasn’t on the menu!

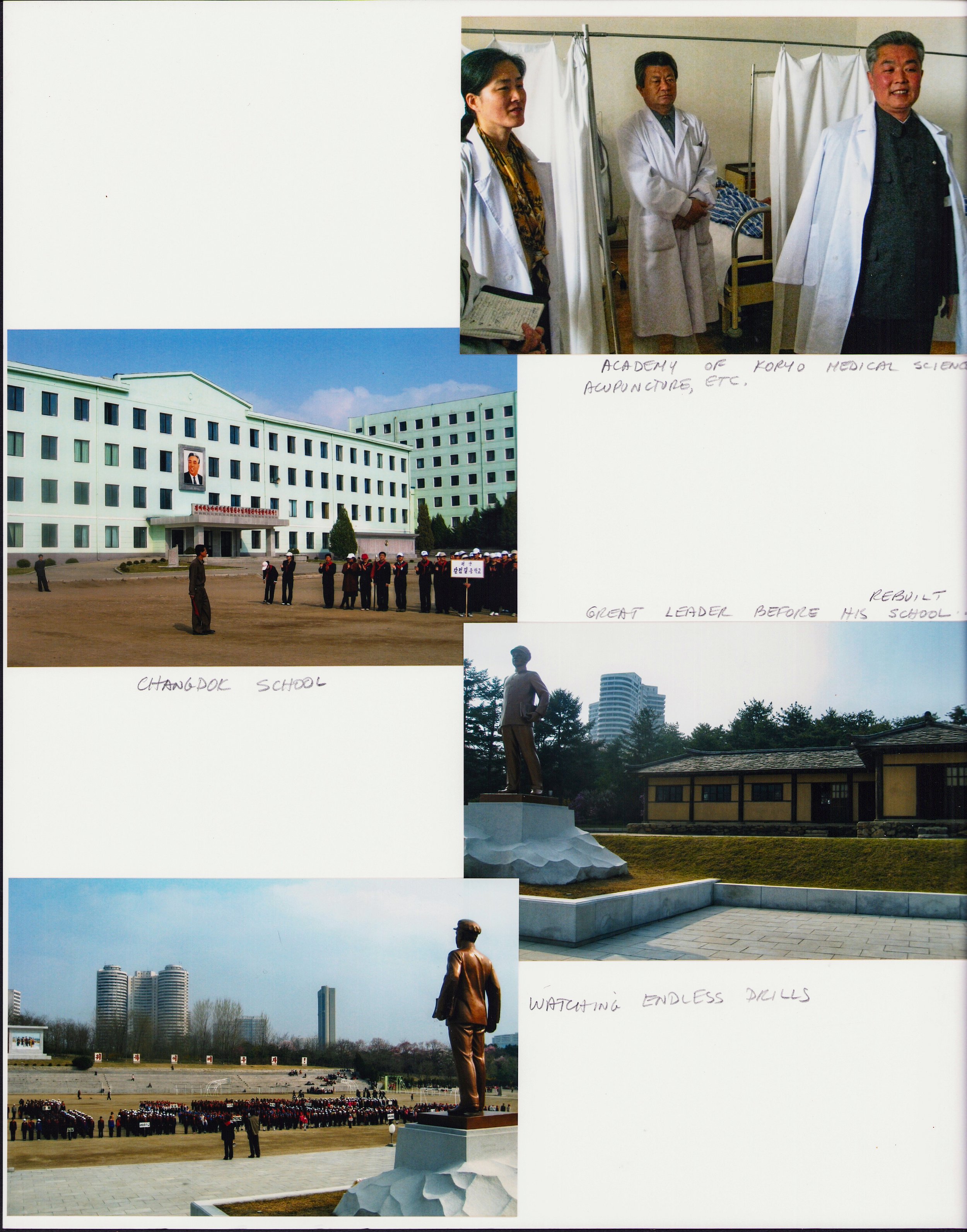

So our Delegation members contented ourselves with trips to schools, museums, arts academies, performances, medical facilities and monuments. These were interesting, fairly predictable and mildly annoying, since the information was always so positive about the Great and Dear Leaders, and the attitude toward the US was always so negative. We also kept running into the same group of Americans wherever we toured, and in comparing notes, realized that we all saw the same sights, with few variations. But we did learn a lot, from things both said and unsaid.

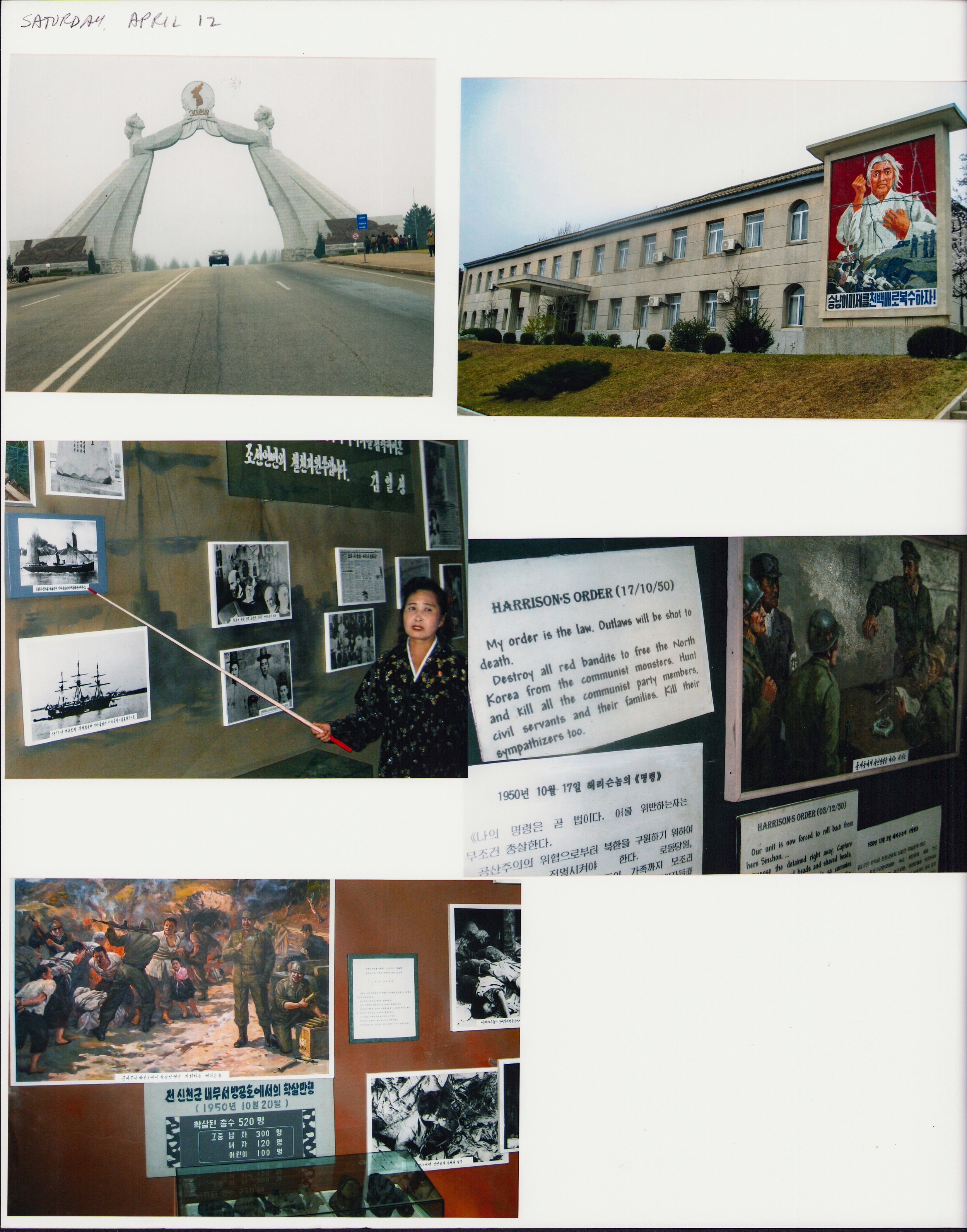

The universal theme we heard everyday and everywhere, is that the US has been historically belligerent and continues to threaten North Korea. At the Victorious Fatherland Liberation Museum, run by the Army, we were harshly lectured that the US decided to split Korea after WWII for its own convenience, started the Korean War as the first step in its imperialist goal of ruling the world, committed all sorts of atrocities, and continues to prevent the reuniting of the two Koreas by its military presence since 1945 at the DMZ and in South Korea, today numbering 30,000 troops. Partial documents and photos, including such things as the apology by Gary Powers for the 1968 Pueblo incident, are used to support these so called “facts” about U.S. imperialism.

With this manipulated perspective, the DPRK keeps itself on a war-time footing since it expects the US to invade it at any time. The North Korean population is ripe for such propaganda, since during the Korean War, North Korea lost 25% of its population, or 2 million of its 8 million people. Moreover, its cities were flattened, mostly by an extensive firebombing campaign. The country has never totally recovered, physically or psychologically.

I’ll add here that it was hard for me to grasp the extent of the presence of the Army in North Korea, the fourth largest in the world estimated at 1.2 to 2 million members (out to a population of 22 million). Many students and workers wear olive-drab uniforms and I was not skilled at recognizing the differentiating insignia. Moreover, we saw many groups drilling in parks and squares for various governmental shows. A military air pervades the country. One wag stated that the North Koreans sleep 1/3, work 1/3 and drill 1/3.

The country also sports ubiquitous banners, urging North Koreans to be self sufficient and to be prepared for an invasion. I was glad I couldn’t read them, and our minders were reluctant to translate them. This invasion preparedness was further fueled when George W. Bush put North Korea on the Axis of Evil list. Kim Jong Il used this insult as an excuse to build up his military, and further develop nuclear weapons. I’ll confess that we shocked our minders when we told them that there was little chance of a US invasion since North Korea doesn’t have any oil!

These themes that focus on the supposed belligerence of the US, that the US started the Korean war, may invade anytime, and is preventing the reunification of the two Koreas, are continually repeated to the populace and visitors. Moreover, these clumsy attempts at our reeducation, were conveyed in physical discomfort. The Liberation Museum, and most of the buildings we visited, were very cold and showed mold. We were told that the heat was turned off April 1, but in fact, because of a fuel shortage, many of the buildings are never heated, despite frigid winters. Visitors talk about attending meetings in the DPRK and having to wear their hats, mittens and coats all the time.

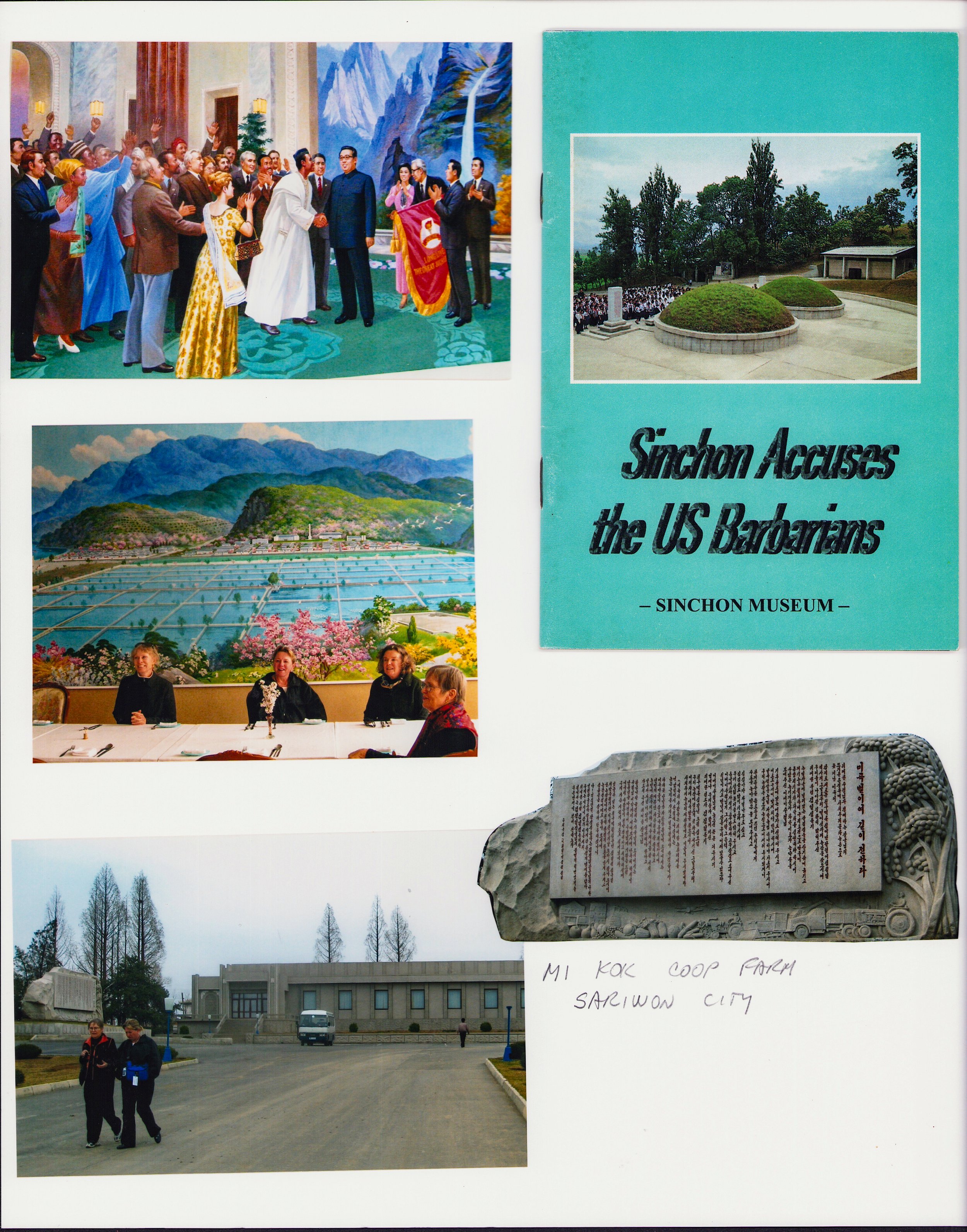

This berating of the US reached a peak for our group at Sinchon Museum in the south, dedicated to the supposed US atrocities during the Korean War. The guide was relentless in her scolding, and the photos of torture and mass killings were sickening, although I kept feeling that these were not American army methods of killing. In fact, when I returned home, I did a bit of research, and read a highly controversial book about Sinchon, by a Korean-American author who said that the torture and murders were largely perpetrated by the former landlords who had been dispossessed by the Communists. This interpretation makes more sense to me, not that I think our military is faultless.

I believe that part of North Korea’s obsession with the US threat is that it cannot admit that the Communist takeover after World War II was not easy, quick and universally supported. Since the North wants reunification, as do many in the South and in this country, the North cannot afford to blame the South for its problems. So the US military role in the Korean peninsula, makes for a convenient and believable bogeyman.

Such rigid standoffs seem to go both ways, I think. Our putting the DPRK on the Axis of Evil list, suggests our black and white approach to relations with them; hardly helpful in negotiating nuclear disarmament. Part of the US problem, I believe, is the fact that we do not have diplomatic relations with the North, only a cease fire, which suggests a permanent state of war. When we were briefed by our Embassy in Seoul before traveling to China and on to Pyongyang, it seemed that much of our embassy’s information about North Korean conditions comes secondhand, from refugees who escape to South Korea. The South gives each refugee $30,000 to resettle there, a fortune for a Northerner. I am sure that countryside conditions in the North are harsh and dangerous, but I also believe that these refugees are capable of telling us whatever they think we want to hear.

In light of the US arms length relations with North Korea, and our press view that the country is so dangerous and remote, I was surprised by the number of American NGO’s or non-governmental organizations and church groups who regularly travel to the DPRK, and who provide a substantial amount of relief. Many of these leaders are Korean-born, Christian and ministers.

A most impressive NGO head I met is Dr. Pilju Kim Joo, formerly of the University of Minnesota. This 71 year old dynamo was born in what is now the DPRK, grew up in the South and studied agriculture in Seoul. She came to the States to study seed science and received her PhD from Cornell. In Minnesota, she taught and worked for Northrup King and Pioneer Hi-Bred. Because of her seed expertise and her husband’s animal science knowledge, the couple was invited in 1989 to help North Korea farmers.

Today Dr. Kim Joo runs four cooperative farms in the DPRK, and has used Minnesota animal semen and plant seeds to build up sustainable agriculture. Her Agglobe Services International project is considered the first large-scale North Korean venture in market socialism. She is trying to turn the farms into model self-sufficient communities, able to feed their residents, and produce enough cash crops whose revenues can enhance community institutions such as schools and medical facilities. As she testified before our Congress: “A hungry stomach knows no ideology. Unless there is cooperation, there is no dialogue, and in the end no change.

North Korea is particularly ill suited for agriculture, because of its terrain and climate. The DPRK is located between 38 and 43 degrees north in latitude, equivalent to northern Iowa and southern Minnesota. It has a dry winter climate with harsh Siberian winds, and is very mountainous. With no oil production, there is no fuel to heat and light homes, operate factory machinery or coal mines. The factories built by the Japanese during 36 years of occupation and 8 years of Pacific War are outdated and in need of repair. Trade is limited because there are few products to export, and because of US economic sanctions. Ironically, the South was the traditional agricultural breadbasket for the country. Now, of course, it is a manufacturing powerhouse, the 11th largest economy in the world, that imports much of its food. Life expectancy for the 22 million men and women in the North is 60 and 69, respectively; in the south it is 75 and 82 for its 49 million people.

North Korea suffered famines in the 1990’s and seems on the brink of starvation today, particularly in the countryside where there may be just one meal a day, according to Young Nam Kim, my violinist friend. Young Nam remarked that on his 2008 visit he saw more trees in the countryside than he had seen four years ago. At that time, he said, people were eating everything they could on the trees, then using the wood for fuel. He said that up to 2 years ago the people in Pyongyang were mixing sawdust with flour to stretch it.

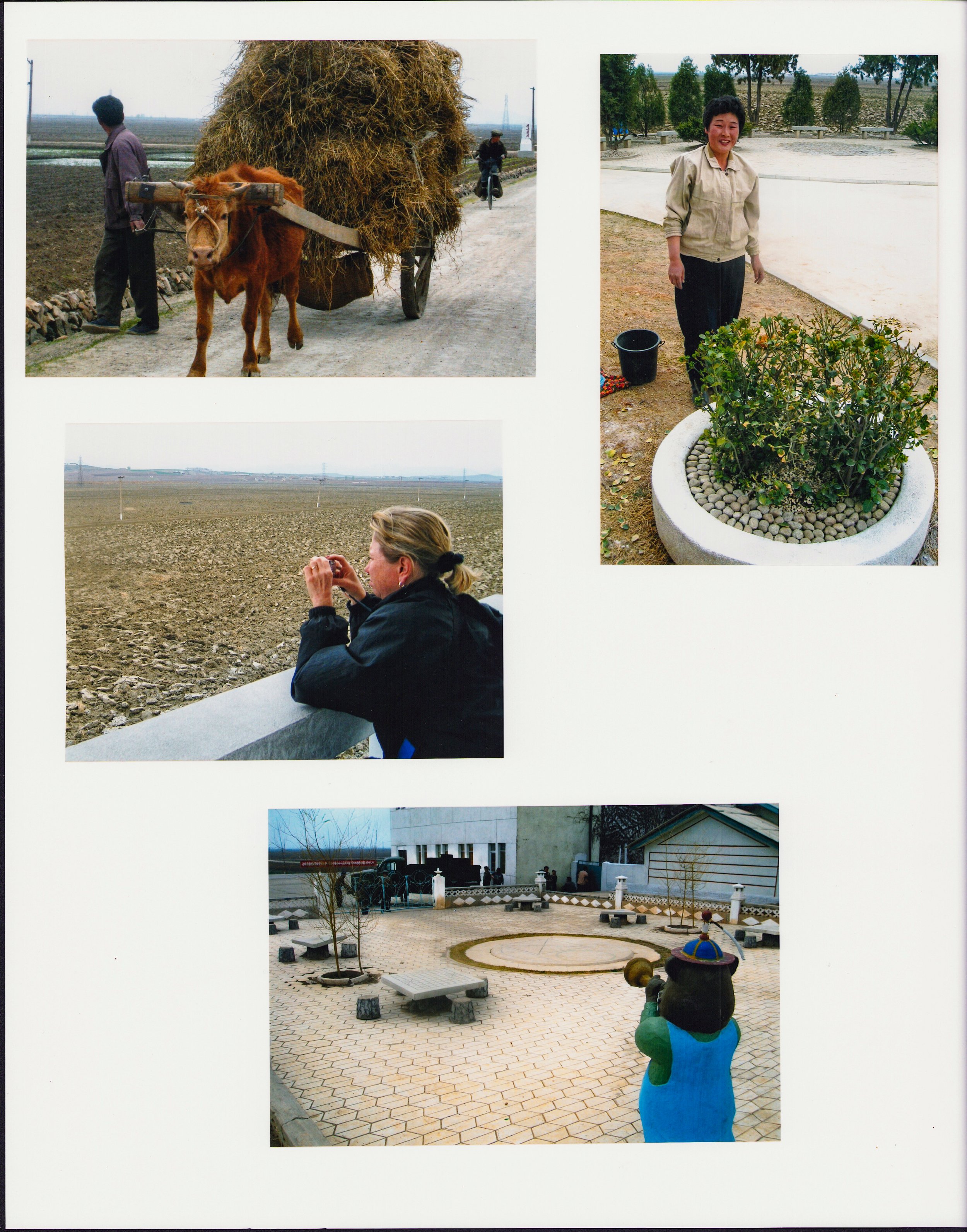

Some books and articles describe North Korean children retarded by poor nutrition, too weak to go to school. The farms we saw had little commercial fertilizer or machinery. The farms were out of Millet paintings, with people working into the dark to break up and hoe the soil with crude hand implements, piles of night soil and kitchen compost waiting to be worked into the fields. North Korea can’t afford to buy fertilizer or enough seeds, according to our guides. One of our guides who works as an agricultural advisor, told me that the country would, with luck, be able to produce 60% of the wheat it needed for the year. As Dr. Kim Joo said to me, it seems that the years they have fertilizer, they get poor weather—floods or drought; years with good weather haven’t had the fertilizer to maximize production.

I earlier mentioned meeting some American Christian ministers on the trip, lead by Dr. Syngman Rhee, a Virginia minister who happened to be a cousin of South Korea’s first president of the same name. These ministers provide flour to the North Koreans, and have also built noodle and bread factories to help alleviate starvation. We kept meeting them during our week in the DPRK, and Dr. Rhee commented that more Christian churches in North Korea were offering regular services since his last trip in 2007. There are 10,000 Christians and 500 house churches in North Korea, as well as 3 public churches in Pyongyang offering services. Pyongyang was once known as the “Jerusalem of the East”, and South Korea is still 50% Christian.

Another surprise to me was the amount of South Korean investment in the North. In the US press we read about the Chinese border factories where North Koreans work, but not about the huge factories that the South is building around Pyongyang. The well educated, cheap labor in the North is an economic magnet, coupled with the fact that many of the South Korean executives have relatives or family homes north of the DMZ. For 10 years South Korea has funneled billions of dollars to the North for new factories, hotels and food, and millions of South Korean tourists have poured across the border. Some policy wonks posit that the North encourages good relations with the South to destabilize US-Seoul relations. Last month the North asked the South Korean factory owners in Kaesong, in the North, to leave; the wonks say that signals the North’s desire to work more closely with the US. And so it goes.

Despite the food shortages, all the North Koreans we saw looked trim and healthy. (In fact, when we reentered China, they all looked pudgy; and when I hit Chicago, everyone looked obese!) However, Pyongyang is not a good measure for the whole country, since it’s 2 million inhabitants are approved to live there. We noticed few elderly people, and only later did I learn that because of the perennial fuel shortage, the elevators seldom worked in the high rises. I can’t imagine walking up 20 stories, even once a week!

While the capital’s housing looked quite good on the outside, in a Soviet-realism sort of way, we heard that in many there were only communal toilets, little or no running water, and no bathing facilities. Many have to walk to public baths, particularly tough if you have no elevator.

We also visited a few hospitals that practiced Western and/or Eastern medicine. While we had to don white coats and slippers to tour the facility, I couldn’t find any soap in any of the bathrooms. The lack of equipment in the rooms and medicine on the shelves spoke volumes about the meager resources of health care professionals. And we were seeing the model medical facilities!

Another bit of medical information I picked up was from a Mongolian doctor who worked for an NGO which offered inoculations throughout the country. He said that the North Koreans were the most compliant in the world, in terms of coming in for their shots. He said that immunization against TB and other third-world diseases caused people to don their native costumes, usually reserved for national holidays, and wear makeup to the makeshift clinics—even the children. Tuberculosis, by the way, is a huge problem in North Korea, affecting at least 5% of the population.

The French NGO worker whom I mentioned earlier, commented that although the DPRK is a strange place in many ways, things were so much better than when she had arrived 3 years ago. Pyongyang has been renovated, with more shops and restaurants, more cars and mobile phones, She said that foreigners who hadn’t been there for 10 years, thought it looked like an entirely different country. Hard to imagine.

But then again, its hard to imagine that until the mid 1970’s, North Korea had a stronger and bigger economy that the South. Today, the economy is widely viewed as broken. The North leadership has reportedly expressed the need to reduce military expenditures to allow economic growth. Such growth is critical to improve its bargaining position with the South for reunification, and ensure it is not completely absorbed by its capitalist neighbor.

There are some signs that North Korea may follow the path of Communist China in developing a market economy, or what it calls “real gain socialism.” There are now 2 to 4 markets in every city, with 19 in Pyongyang—the biggest of which attracts 10 to 15,000 people a day. These bottom up changes are mirrored at the top: in 2002 the government passed economic financial reforms, and the social hierarchy is being transformed by the influence of money, according to scholars.

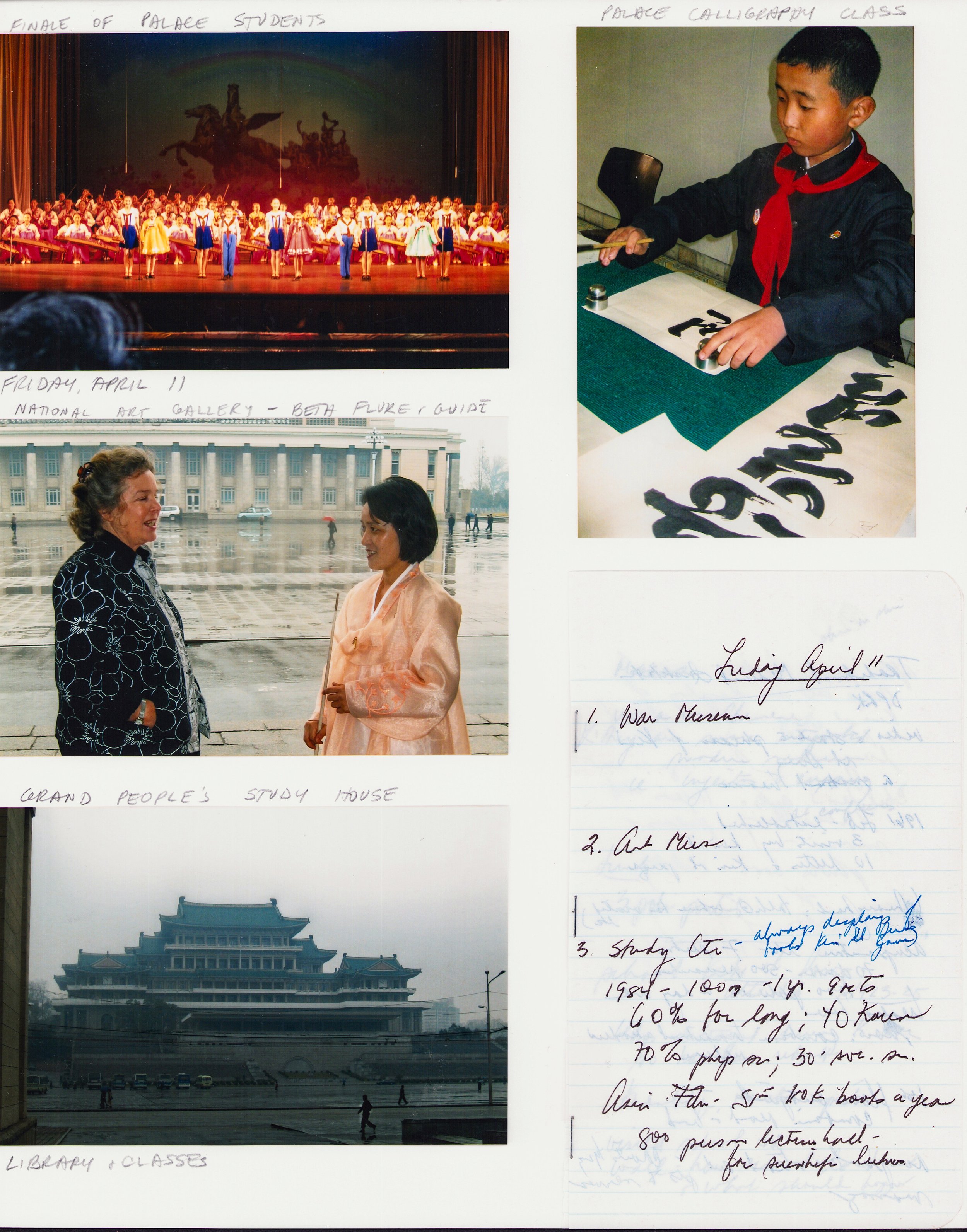

I mentioned earlier that the 2 million residents of Pyongyang are vetted to live in the capital. The government also invites the beautiful people of the country to live and be schooled in Pyongyang. Talent scouts recruit the best athletes, musicians, artists, acrobats and students to move to Pyongyang for training. We saw many model schools for children who put on remarkable performances in their impressive, although not lavish facilities, much like the China we visited in 1982. And then there were the skating, circus, dancing and singing performances each day in one people’s hall after another. All acts were flawlessly executed, accompanied mostly to Korean music, played on both native and Western instruments.

Speaking of music, I also had the opportunity to visit a gorgeous new conservatory where I heard students perform Western classical music, including opera, with great technique and feeling. Korean music on native instruments was likewise beautifully offered by the country’s best and brightest.

Many North Koreans also expressed pride and excitement about having been given tickets to hear the New York Philharmonic two months before. Several were impressed to learn that several of the Phil musicians who coached the conservatory students were my friends. My New York friends, in turn, told me that they had expected much poorer musicianship in the country, and were thrilled with the caliber of individual and ensemble playing. By the way, Young Nam Kim told me that when he asked a DPRK musician about the NY Phil performance, the North Korean replied: “We play as well.” After hearing some of the orchestras there, Young Nam said he agreed—the North Koreans are phenomenal musicians.

On the other hand, I had come to the Conservatory with an offer from a London friend of mine to recruit North Korean music teachers and students for her string program. Since Great Britain has formal diplomatic relations with North Korea, exchanges are much easier. However, I drew only polite interest from the North Koreans, as well as a list of tasks for the London organization. I doubt if anything will ever happen.

The last topic I’ll discuss, is the treatment of the Great Leader, the deceased Kim Il Sung who is his country’s permanent President, and the current ruler, Kim’s son, Kim Jong Il, the Dear Leader. I have chosen to describe my impressions of them at the end of my talk, because their presence is so pervasive and startling, that their cult of personality can overwhelm one’s entire view of the country.

I’m not sure I can adequately convey the enormity of the Kims’ role as background, foreground and everything in between. You go nowhere without seeing or hearing about them. The Soviet Union and China in their Communist heydays were pikers by comparison.

You have the usual panoramic paintings in all buildings showing Kim Il Sung, the Great Leader, sometimes joined by his son, Kim Jong Il, the Dear Leader. The Kim portrayals are right out of the Lenin-art playbooks: Kim with children, Kim with workers, Kim looking into the sunset. The facial expressions of the leaders are kind but determined. Who couldn’t love these guys, even if the current Dear Leader wears heels and blow combs his hair?

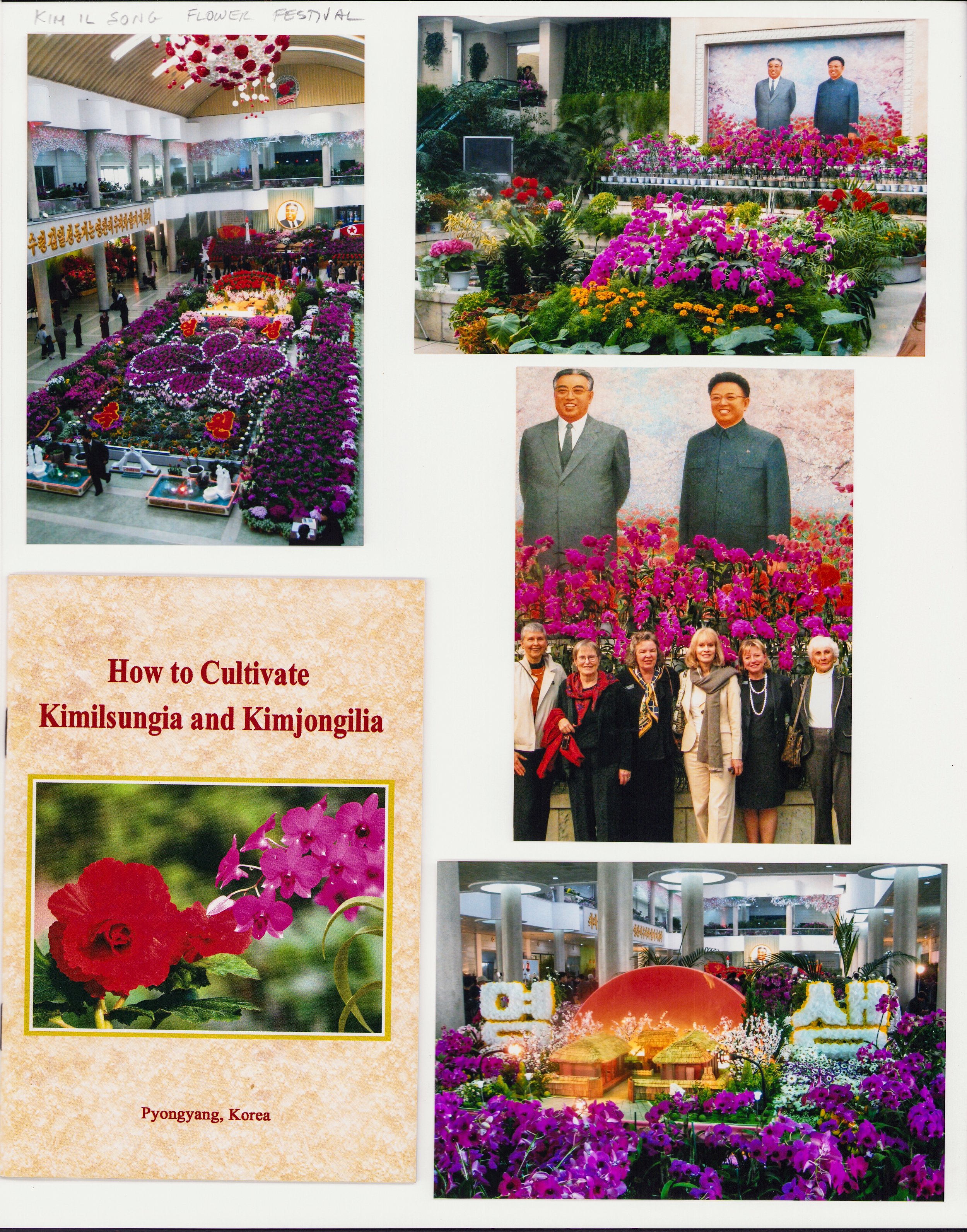

By the way, placed before each painting and statue, there would be potted orchids and giant begonias; these flower species have been hybridized in honor of the Great and Dear Leaders. And most of the Kim portrayals included their very words on the subject at hand, in their handwriting, magnified and carved in stone.

But the adoration/deification goes further, in ways I had never seen before. Everywhere we went we were immediately shown objects owned or given by the Kims to the institutions. For instance, in the state Library or Study House, as it is called, the books that the Kims had either written or owned were separately encased in each room; lighting, photos and plastic flowers added personal touches. The lesson to us seemed twofold: the Kims are great intellects and they want to share everything they have with the people.

The Kim cult still goes further. Every place we went, and I mean every place, we were shown where the Kims had visited and what they had said, no matter how pedestrian or obvious. For instance, a map at a model farm showed at what points the Kims had spent time, on what date, and what they found interesting. At a maternity hospital our guide pointed out the patient and administrative rooms that the Kims had visited, noting the date of their visits. The underlying point to us was that the Kims really care about their people and wish to ensure that each facility strives to be the best.

Gifts to the Kims were also another opportunity for celebration and enshrinement. One middle school had a large room devoted to carefully done books and art work the students had given to the Kims, and that the Kims, in turn, generously gave back to the school for display. The capstone display facility in the country is the International Friendship Exhibition, a mammoth repository of over 200,000 state gifts given by 165 countries to the Kims. Gifts are grouped by country of origin in over 200 rooms, and include railway cars and automobiles. The guides were careful to point out some modest American gifts, a small bowl from Jimmy Carter and a letter from Billy Graham. The underlying point seemed to be that most of the world leaders admire and respect the Kims.

The country seemed particularly awash in Kim adoration when we were there in mid-April, since April 15 is Kim Il Sung’s birthday. People from throughout the country came to visit his various shrines such as: Mangyongdae, his native home, his schools, his gigantic mausoleum with moving sidewalks, and his many statues. The women were particularly lovely, wearing the choson, or vibrantly-colored native dress. In fact, they looked like the waltz of the flowers, gliding through gardens or ascending monumental staircases.

The ultimate experience in Kim Il mania, and one that I must confess I heartily enjoyed, was his birthday celebration in Kim il Sung Square on April 15. Over 40,000 North Koreans, the women elegant in their chosons, danced native dances in unison. Some were like massive square and circle dances; others partner steps. Guests could join in, and I did. My partners, each chosen by their factory or school to participate, were gracious and tolerant as I tried to learn the steps. It was a thrilling time, and totally unlike any experience I had ever had before…or will have again. Circuses, even if bread is in short supply, are not all bad.

The Kim il Sung birthday dance was a fitting end to a pleasant, interesting, highly choreographed week. As a result, I cannot admit that I now deeply understand North Korea, because I was never permitted an in-depth view of anything. I don’t believe the North Koreans when they say they have no problems and just want peace, nor do I believe the American government view that most North Koreans are repressed and miserable. It is also difficult to believe that the two Koreas will reunite soon, given that their economies and value systems are so different and continue to grow apart.

In the meantime, I’ll be content to read the paper more intelligently, and give small support to people like Dr. Pilju Kim Joo who is trying to make daily life in North Korea more bearable, while we all wait for change.

April 7, 2008 - Seoul; Modern piano in hotel lobby; Hwa Young Lee (center), our guide, with LA friend (L) and Reunification leader; Nice Seoul shopping street; Dr. Kim Joi, retired UMN plant expert with 2 experimental farms in DPRK.

Old and new mix in Seoul; Lovely Mary Pomeroy & Jill Christiansen; Gyeongbokgung Palace; Changing of Guard; Imperial stroll through Palace grounds.

Pagoda & crafts cottages in Palace compound; Beth Fluke and LLH; Ancient Korean statues (replicas?) on Palace grounds; Famous bridge en route airport.

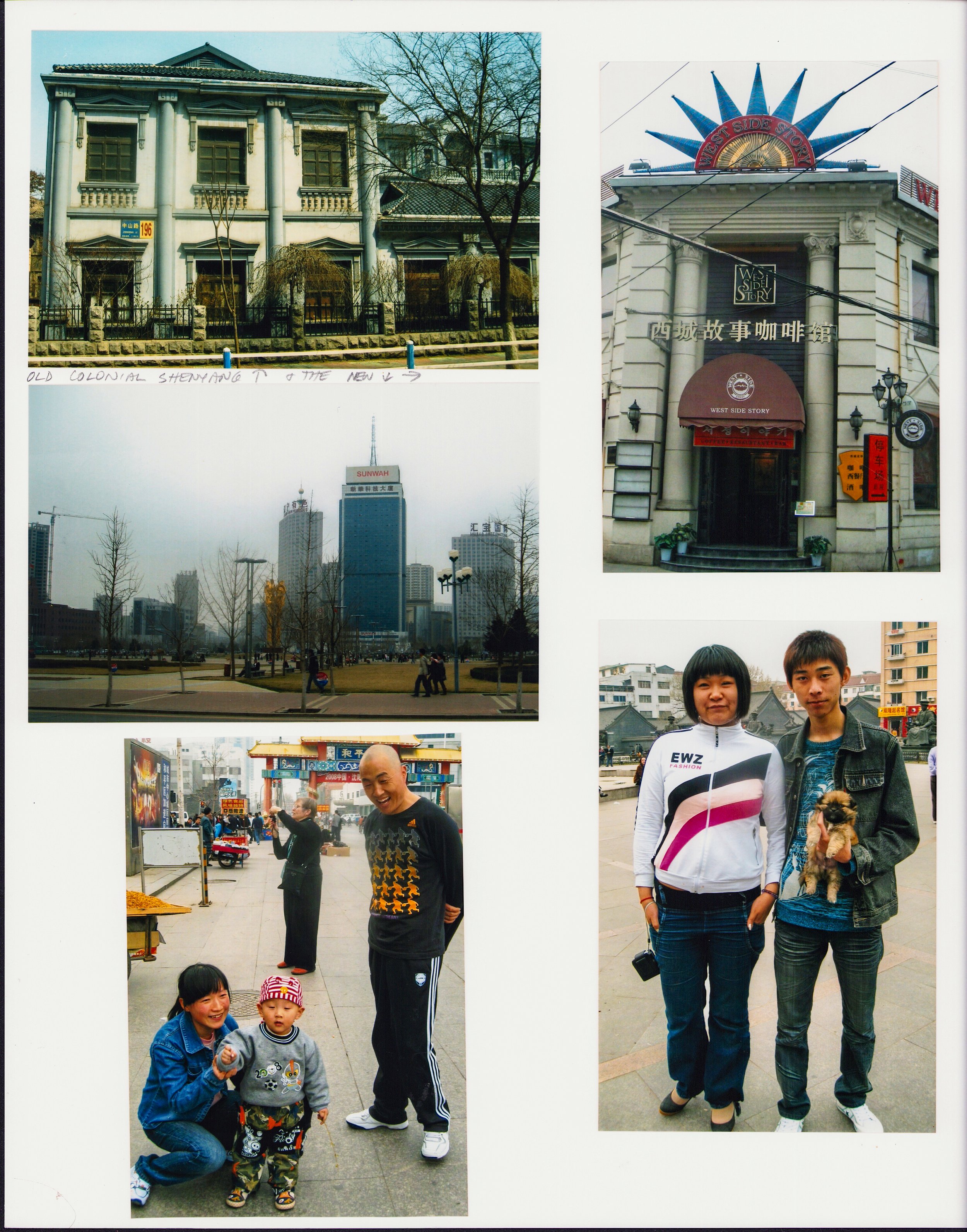

April 8-9, 2008 - Shenyang, China; Beth at Imperial Gate; Stunning Manchu Imperial Palace; Like Forbidden City in Beijing without the crowds; Our small Delegation (DPRK limited our number).

Charming gazebo; Lovely interior garden.

Royal chambers.

Old Colonial Shenyang and the new.

Communist Heroes' Headquarters / Museum; Manchu Emperor's Park.

April 9 - Magnificent Qing Tomb.

Really fresh seafood; Plastic samples; Dried fruits and nuts vendor.

Late afternoon, April 9 - Pyongyang; Our guesthouse, Kobangsaw; Lake by guesthouse created by damming river; Lobby; We meet with Mr. Kim (by Jill), Mrs Lee & Mr O (mirror) to review our itinerary.

April 10 - We first visit Mangyongdae, Great Leader's native home; Women float like beautiful flowers to tour home; Kim Il Jong's well. Water promises health so I imbibe.

Postcard arrived several weeks after in home; Pyongyang subway; Very Soviet style stations.

Pyongyang Maternity Hospital; Hospital entrance; As guests we wear lab coats, but no soap in any bathrooms; The Great and Dear Leaders. Ubiquitous; Girls are center of this fountain. Boys the other.

Lab; Mothers of triplets, twins get extra State support; Dental care also offered; Carol Whitmore. Sanitary, hands=free mode to talk with docs & patients.

We meet with hospital leaders after tour; Lovely cherry blossoms abound; View of Pyongyang from hospital 2nd floor; Sylvia Sabo, pair o' docs, Jill; Minyea Handicraft Exhibition Hall.

Changwang Kindergarten; Children live in school and go home Sundays; Great and Dear Leaders and their flowers at school entrance; Model children do origami via TV instruction; Leaders gave these stuffed animals to school for teaching purposes.

Dance class; Route to cafeteria where children learn N Korean fruits.

Indoor gym. G & D Leaders gave; Finale performances; Cafeteria.

Mangyongdae Students and Children's Palace; We climb stairs past bronze animals, and Great Leader with Happy Children; Palace Lobby; View of city from Palace Plaza.

A younger Great Leader; Calligraphic note by Great Leader chiseled and gilded in stone; Palace classes; Talented children from around country are trained here.

Finale of Palace students; Palace calligraphy class; Friday, April 11 - National Art Gallery. Beth Fluke, guide; Grand People's Study House; Library and classes.

Kim Il Sung. Study Center Lobby; Great and Dear Leaders' book on each discipline would be enshrined separate from rest of collection; View of city from center terrace; English language class; I am shown how desk operates.

What a way to start the day! Plus no heat in this Army Museum; Captured plane, one of many; Pueblo Incident; 360º diorama; Premise: US stared war as part of strategy to take over world.

Changdok School; Academy of Koryo medical science, acupuncture, etc; Great Leader before his rebuilt school; Watching endless drills.

Saturday, April 12.

Mi Kok Coop Farm, Sariwon City.

Sunday, April 13 - International Friendship Exhibition.

Mt. Myomyang.

Buddhist Temple.

Arch of Triumph; Grand Theatre; 'Victory' - Fatherland Liberation War; Pothong Gate.

Grand Study House.

Kim Won Gyoun Conservatory.

Kim Il Song Flower Festival.

April 15 - The Great Leader's Birthday

We are about to leave for the plane.

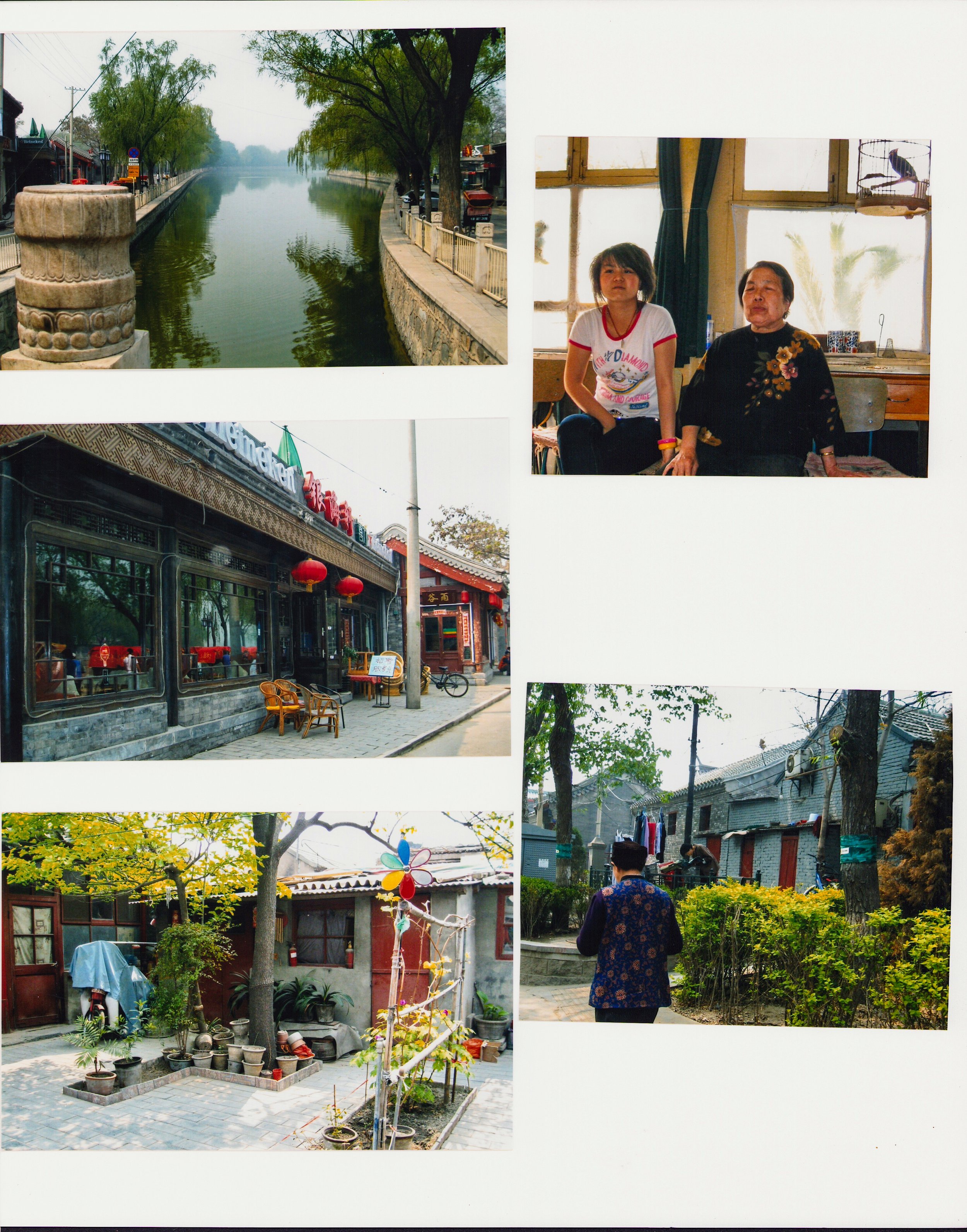

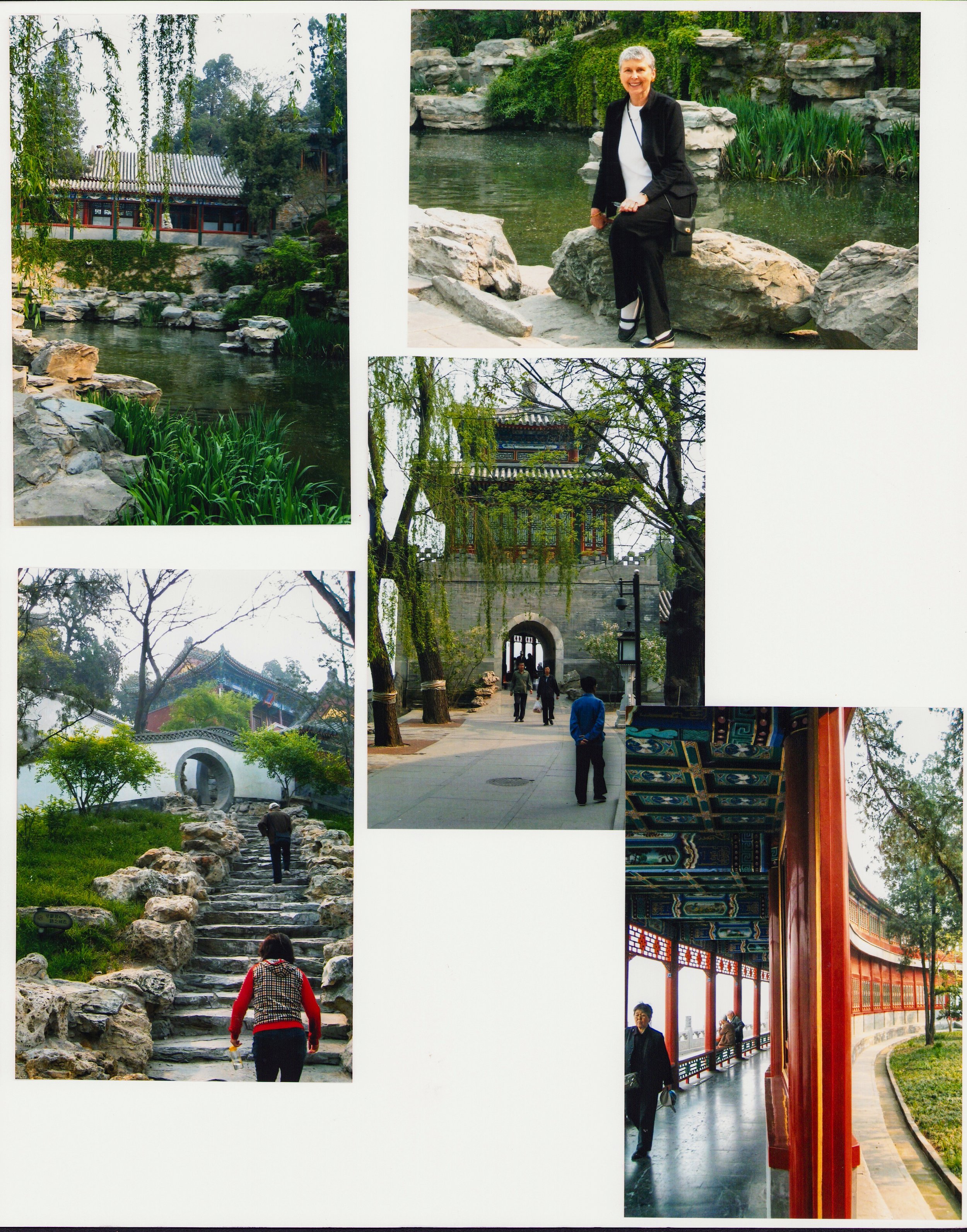

April 17 - Beijing; Drive by of Olympic Village; Beihei Park; City of Harmony.

Line dancing.