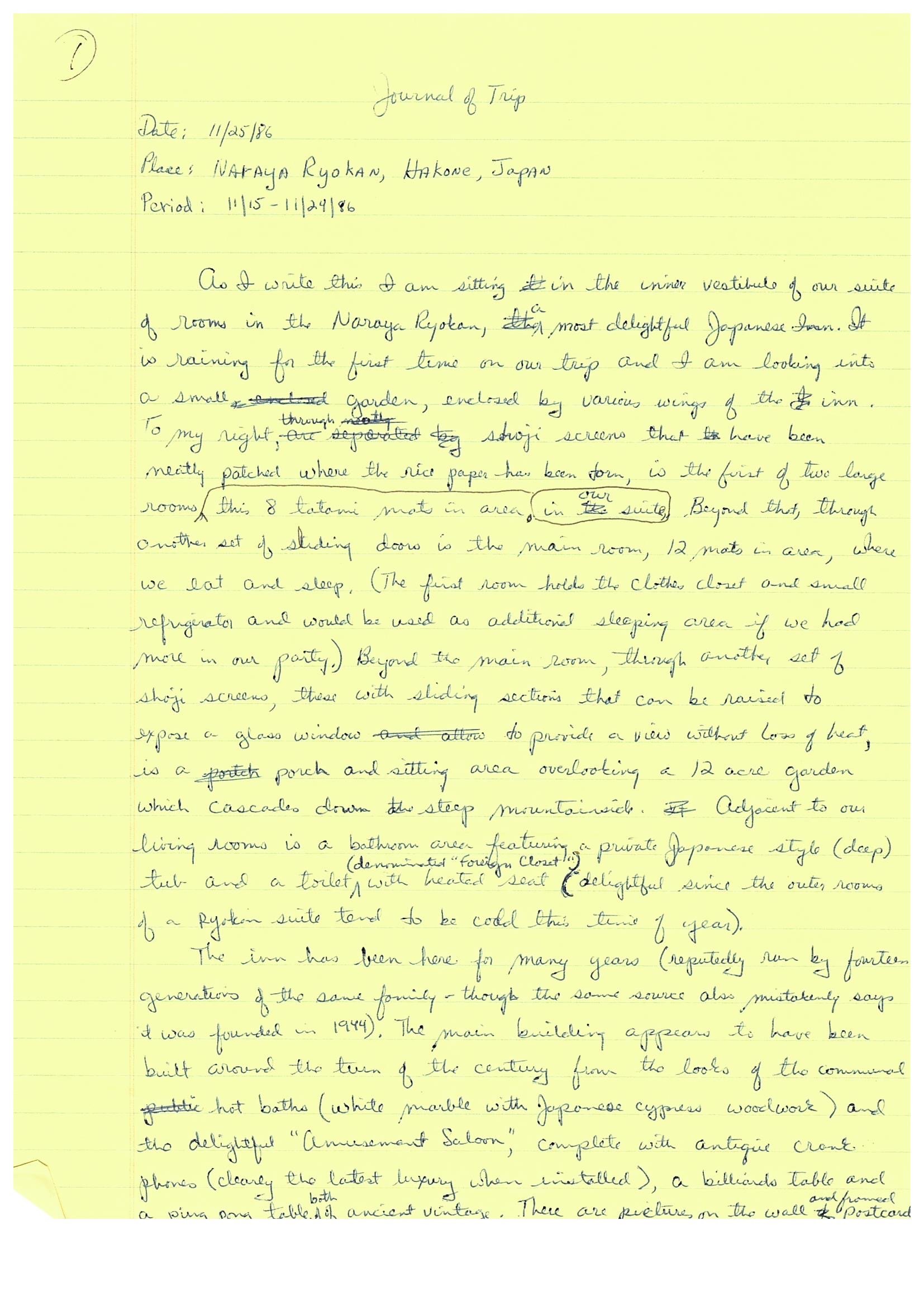

Japan Trip, 1986

by Jack Hoeschler, 11/25/86

PLACE: Naraya Ryokan, Hakone, Japan

PERIOD: 11/15 – 11/24/86

As I write this, I am sitting in the inner vestibule of our suite of rooms in the Naraya Ryokan, a most delightful Japanese inn. It is raining for the first time on our trip and I am looking into a small garden, enclosed by various wings of the inn. To my right, through shoji screens that have been neatly patched where the rice paper has been torn, is the first of two large rooms in our suite; 8 tatami mats in area. Beyond that, through another set of sliding doors is the main room, 12 mats in area, where we eat and sleep. (The first room holds the clothes closet and small refrigerator and would be used as additional sleeping area if we had more in our party.)

Beyond the main room, through another set of shoji screens, these with sliding sections that can be raised to expose a glass window (which provides a view without loss of heat), is a porch and sitting area overlooking a 12-acre garden which cascades down the steep mountainside. Adjacent to our living rooms is a bathroom area featuring a private Japanese style (deep tub and a toilet (denominated “Foreign Closet”) with heated seat (delightful, since the outer rooms of a Ryokan Suite tend to be cold this time of year).

The inn has been here for many years (reputedly run by 14 generations of the same family – although the same source also mistakenly says it was founded in 1944). The main building appears to have been built around the turn of the century from the looks of the communal hot baths (white marble with Japanese cypress woodwork) and the delightful “Amusement Saloon”, complete with antique crank phones (clearly the latest luxury when installed), a billiards table and a ping pong table, both of ancient vintage. There are pictures on the wall and framed postcards dating from the early part of the century, showing early trains and tour buses bringing tourists to this traditional hot spring onsen (spa) in the mountains near Mount Fuji. The inn has hosted the Emperor and his family and has been a regular stopping place for imperial and shogunate travelers passing through the Hakone Gate along the Tokaido Road between Tokyo and Kyoto.

Even though we seem to be fairly high in the mountains, and it is now late November, the weather is still mild. The Japanese maples are a song of red, and orange camellias are still blooming, and the bamboo is still green. There are also palm trees in the garden. One of the owners told us it only snows here about every three years. Japan has numerous biospheres depending on altitude and proximity to the sea, as well as latitude.

We received both dinner and breakfast in our suite (Manny and Fritz join us from an adjoining suite for meals). The maid who serves us is truly the guardian of both us and our rooms. Dinner consists of seven courses of exquisitely arranged portions in about 12 containers, all served in a definite order (with rice last – if you eat too much rice, it is sometimes regarded as a sign that you don't like the food). We commented at dinner that the presentation in Japan contrasts greatly with the pell mell rush of food you receive in China. Clearly the Chinese, especially after the Revolution, have forgotten many of the refinements that once made them the model for Japan.

Without doubt the Narayan is a delightful step back into the best of traditional Japanese lifestyle and hospitality. The only thing shockingly modern is the price – $700 a night for the four of us-- the most expensive so far but, regrettably, not by as much of a margin as you would think.

We arrived in Tokyo nine days ago after a reasonably pleasant flight (given a 6:30 a.m. departure and 11-hour flight from Seattle after a change of planes in Chicago - such is the price one pays for a $2,100 around-the-world ticket). We spent the first four days at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, and that is and will be our Tokyo base as we pass through on our various loops around the country. The hotel is large, geared to Western business travelers, and very friendly. The reputation of Asian hotels for wonderful service is being well maintained by the Imperial.

The coffee and tea in the Imperial cost no more than in small coffee shops on the street – $3 a cup. This is typical of the breathtaking prices in Japan since the dollar has fallen so much against the yen. Hotel rooms (without meals) are at least $200 per night and theater tickets are $45 apiece. I just regard it like a much more pleasant and safe version of a stay in New York City and try not to think too much about the prices lest it spoil the trip.

The way we deal with jet lag is to go to bed early and then awaken before dawn and tour the local markets. In Tokyo, the fish market is just on the other side of the Ginza from the Imperial and a wonderful experience. It covers a 16-block area, much larger than the old Fulton Fish Market in New York. Long stringers of frozen tuna are hoisted from boats onto the wharf where they are laid out in rows and marked with identifying numbers. A flap of flesh is cut near the tail of each so that bidders with fishhooks and flashlights can inspect the meat. Between 5 and 6 a.m. each fishery (there are quite a few) auctions the fish individually, starting with a deep bow by the auctioneer to the bidders and the type of incomprehensible hand signals by the bidders that one sees at the Chicago Board of Trade. There is very little noise, save for the voices of the auctioneers.

Further in from the water are many rows of stalls where a vast variety of smaller fish are sold along with quarters of the tuna that are transferred there after the auction for cutting. Everything is very clean, with no smell whatsoever. The squid and octopus are very colorful red and orange, and all are carefully laid out in neat rows in styrofoam boxes packed with ice chips. Further in yet, are rows of stalls where small, neatly packaged sardines and other bite-sized seafood products are sold. Finally come the stalls of hardware, clothing and accessory sellers serving the market as a whole. Throughout this entire area, men run with push carts and motorized dollies piled high with boxes of fish, moving from the outer rows through various processing and packaging stages, to the waiting trucks of restaurants and retail fish markets. As is often the case in Japan, the motors are the noisiest element, since the people are very quiet and considerate of each other with none of the shouting that one associates with New York or Italian fish markets.

We had breakfast in one of the small (14 seat) restaurants at the edge of the market, and luckily found a Japanese man who spoke enough English to help us order. It was so much fun that we went back the second day as well to see more and get some pictures.

Later on our first day in Tokyo we took a half-day bus tour of some of the city sites to orient ourselves. The last stop was at a cultured pearl establishment and Manny Elson, who is 86 and has joined us for the Japan part of the trip, got separated from us during one of the demonstrations. For some reason he got the idea that we had left without him and therefore he struck out by himself to walk back to the hotel (which happened to be about 2 miles away). When we couldn't find him, Linda proceeded to have a nervous fit. Fritz and I are much more trusting of Manny's ability to show up unscathed after such experiences. More to satisfy her than out of fear for Manny, we went to the local police precinct house as well as the American Embassy (which were both nearby) to report the missing person, while she took a cab to the Imperial to see if he was there. After about two hours we had finally filled out all the required forms and the police dragnet was firmly in place. At that point, Manny walked into the Imperial little worse for the wear, but not quite sure of the way he had gotten there. After that, it was early to bed for everyone.

The next two days were spent walking around the city and attending Kabuki theater shows. These go on for four to five hours and are analogous to Wagnerian opera in their tone and pace, though nothing is sung, of course. People bring or buy (in the lobby) box lunches of sushi, fruit to eat these during the performances. Earphones with helpful English commentary and translations are available and even used by Japanese. We have been re-reading the Tale of the 47 Ronin, the second third of which we saw at the National Theater and thus we actually enjoyed ourselves. We will see the last third before we leave in December.

On our last night in Tokyo we went to the home of a retired CPA in one of the suburbs for a home visit arranged by the Tourist Information Center. This is a nice program, and the visit was very interesting. The trip out was by subway and elevated train, a fun adventure in its own right. The CPA lived in a duplex with his daughter and son-in-law in the apartment above. He spoke reasonably good English and had been to the States. His wife and granddaughter (15 years old, going on 12) spoke mostly Japanese. He proudly showed us his watercolors (and even painted one which he gave to us) and played his flute for us. He continues the traditional Japanese respect for active participation in the arts alongside a profession.

After three days in Tokyo, we took a bullet train, local train and two busses north to the Nikko National Park for our first experience in a ryokan. As those things go, our first two nights were spent far up in the mountains at Yunishigawa Onsen, where few western tourists venture. Indeed, we could find no one who spoke English at our ryokan the first night; it took us a little while to figure out the routine and the rules of the game from sheer observation. There were announcements over the PA system from time to time, but we could understand nothing. Luckily, on a recognizance tour Fritz and I noticed a small dining room marked with our name and we knew we wouldn't starve.

Indeed, the food was one of the more interesting aspects of this ryokan. It featured bear meat and salamanders cooked over a charcoal pit in the center of the room. There were countless other dishes as well, but our waiter was without English words for them. He tried, but little was learned. Indeed, we tried to get something to drink several times without success. It was only when Fritz said, “My compliments to the cook,” that the waiter thought he wanted a Coke and we soon had Cokes all around.

The territory around Yunishigawa is very mountainous with the mountainside generally too steep to climb easily. There are small villages (8 to 15 houses) in the narrow valleys. It is amazing to see the efforts the Japanese make to serve these small settlements with roads, power and other services. In addition, they are spending an immense amount on erosion control works high in the mountains where we would never begin to do a thing in such areas in the states.

The scope of this infrastructure effort was most notable when we visited Lake Chuzenji west of Nikko a few days later. There, the entire side of a large volcanic mountain was terraced with erosion retaining walls from top to bottom. The lake is a picturesque volcanic mountain lake released by a dramatic horsetail falls. It is a favorite resort destination of the Japanese that tops off a trip to the temples and shrines at Nikko. These temples date to the 8th century and feature the grave of Shogun Ieyasu (1543-1616), the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the hero of Clavell’s novel. The shrines are noteworthy because of the Baroque architecture of many of them. The simple line of traditional Japanese design is not to be found here. It looks like a take off on the most rococo of Chinese architecture.

It was at Nikko that we learned of the Japanese custom of keeping a book in which the chop of each temple (along with calligraphy done by the monks showing date and place) is kept by pilgrims. Fritz started such a book here and we soon realized that every hotel, train station and city has a chop of its own which can be added to the book. With these, however, you don't get the nice calligraphy. This makes a nice souvenir, and we intend to try to keep the practice up in Thailand and India, if possible.

Incidentally, during the Edo period (1603-1867) the Shogunate did not allow tourism. However, trips to temples were allowed, so during this period pilgrimages became the rage (with everyone keeping track of the shrines and temples visited in their chop books), not so much for religious reasons as for an excuse to travel.

After our country trips in Nikko and Hakone, we spent nine days in Kyoto. We stayed at the Miyako Hotel – Manny and Fritz in the western wing and Linda and I in the Japanese style wing, about a block away through a garden. The boys were happy to get away from Linda's close watch. We did a lot of temples, shrines and gardens but since there are over 1600 temples and 200 shrines, there are plenty left for a return visit. Generally, I liked the Zen temples and gardens best, and could spend much more time in them. It was pleasant being there so late in the season after the tourist crush, when most westerners are gone. The weather was still quite pleasant and most trees still had their leaves. Interestingly, many of the magnolia and rhododendron bushes were still in bloom.

One evening in Kyoto, we had an interesting dinner with Bardwell Smith, professor of Far Eastern Religions at Carleton College. John Musser had alerted me to the fact that Professor Smith was spending the academic year in Kyoto and wrote us an introduction. Dr. Smith is doing research on ways Buddhists are dealing with the abortion issue. Buddhism regards life as beginning at conception, and generally parallels Catholic views on the taking of life. Yet abortion is a major form of birth control in Japan because they fear the side effects of the pill and men are resistant to the use of condoms. According to Smith, the average Japanese woman has had two abortions before menopause.

Apparently, a few temples have developed reputations for counseling women who have had abortions. But generally, the male dominated priesthood does not seem to get involved in this issue. Professor Smith pointed out that many of the Jizo figures that we see outside Buddhist temples and elsewhere (and associate with votives for childhood or a child), are really placed for an aborted child. The Jizo figure is a gateway or guardian figure which helps a soul, especially that of a child, through the underworld. Little shrines with numerous Jizo figures – little crude doll shapes (often not more than a tombstone with a head), many with bibs and sometimes hats – show up along country roads, city streets and in temple precincts. Clearly Smith is on to something, and it will be fascinating to read his write-up.